Leadership in Motion: How the Education Leaders' Experience Is Reshaping South Carolina’s Leadership Landscape

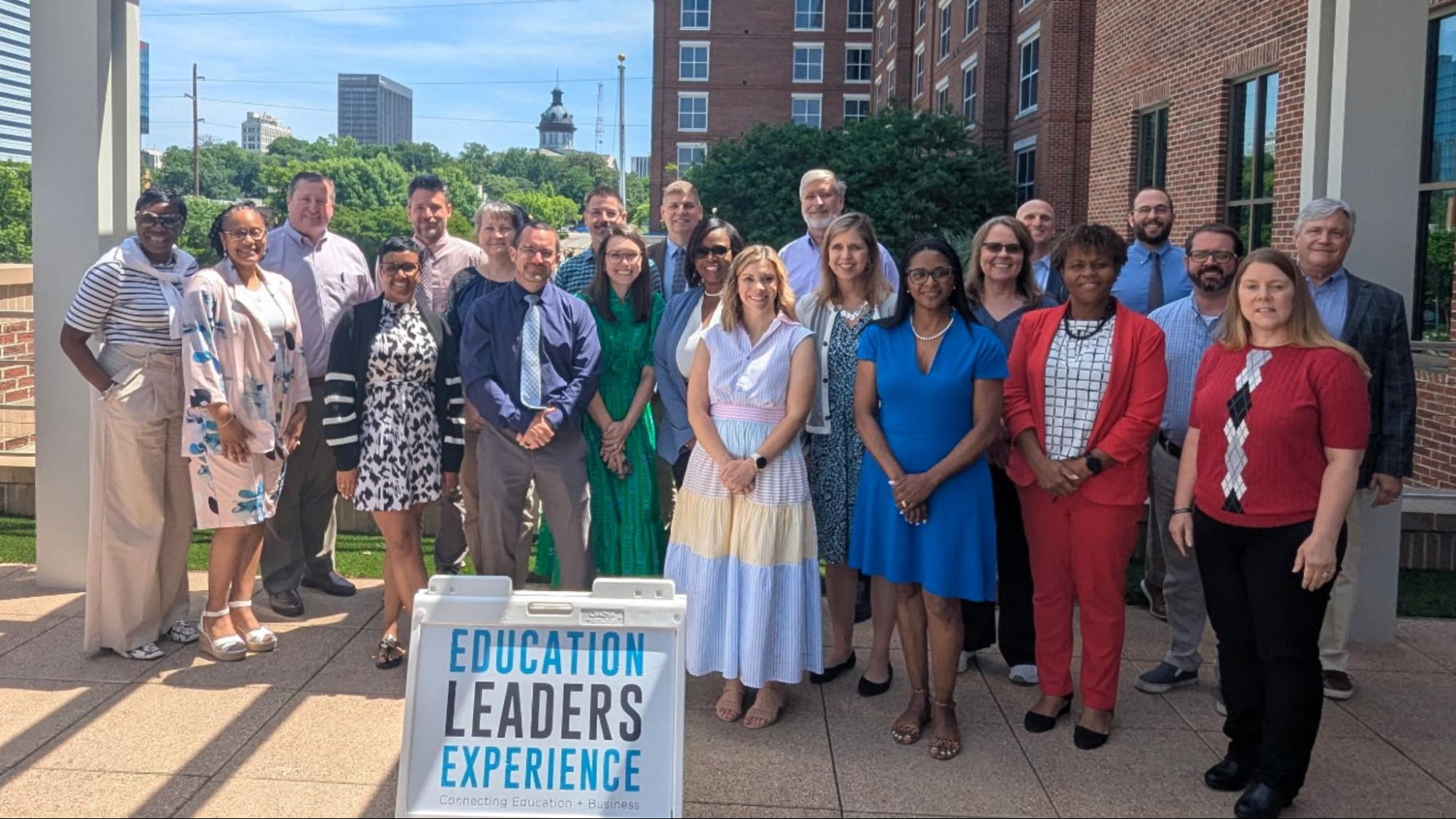

When leaders across South Carolina entered the Education Leaders Experience (ELE), they didn’t just gain new knowledge; they entered a new way of thinking about themselves, their teams, and the work ahead. From seasoned administrators to newly placed district leaders, the Iota Cohort has become a living example of how intentional leadership development fosters transformation across systems.

ELE is not a sit-and-get program. It is a community of practice, a space for challenge and reflection, and a platform where leaders learn not only from facilitators but also from one another.

From retreat sessions and leadership style assessments to micro-credentials and storytelling activities, each experience is designed to stretch participants in ways that lead to sustainable growth.

For LaWana Robinson-Lee, the shift was immediate: “This experience shifted my thinking.” For others, the change was gradual but no less impactful. Felicia Madden reflected, “ELE allowed me the time and space to be around a diverse group of educators to gain knowledge and ideas to take back to my district.”

Participants frequently cited the concept of exposure. Austrai Bradley shared, “Animation studio right here in SC. Mind-blown.” Karla Harper noted, “Each session will allow me to bring back information to my colleagues and, most importantly, opportunities for students. Key Word of the day: Exposure.”

These experiences weren’t limited to professional settings. They reflected ELE’s deeper mission: to build leadership capacity across systems by showing what collaboration and shared vision can look like when people feel connected and seen.

Across districts and roles, four major themes emerged from the voices of participants:

- Community, Networking, and Belonging

ELE built a bridge between educators across regions, roles, and systems. That sense of community mattered deeply for participants new to the state or their position.“Being new to the area, I was able to access this network of talent and knowledge to help me grow,” shared one leader. Another, Kendra Harper, wrote, “As a new resident of the state, this was an excellent opportunity to meet and engage with new leaders.”Education leaders are not afforded many opportunities to expand their networks and perspectives beyond the four walls of their buildings during traditional work hours. ELE provides community building opportunities, creating new curriculum and workforce development opportunities for learners and educators alike.

- Leadership Self-Awareness and Style

Many leaders left the ELE with a new understanding of how they lead and how they could grow. Dr. Carolyn Donelan shared, “The leadership assessments allowed me to reflect on my leadership strengths and concerns. I plan on sharing these results with my staff to discuss ways to flex my style to fit their needs.”Others noted how their styles had evolved. Julia Kaczor reflected, “The ELE ‘What’s My Leadership Style’ identified my strength as Spirited, which shows my evolution since I once was Direct. This change shows my transformation as an instructional leader.”Participants were encouraged not to be defined by one style but to recognize the range of leadership tools available. One participant noted, “The activities we participated in made us rethink what we thought we knew about ourselves.”

- From Reflection to Action

ELE participants didn’t just reflect; they brought the learning back to their districts. Casey Faulkenberry explained, “Moving forward, I plan to use a strategic approach for groups or teams to begin their work by focusing on collective commonalities and then working out to individual needs.”Others spoke about leading with greater purpose and delegation. Inspired by speaker Ron Harvey, Melissa Moore shared, “I plan to lead with less intervention and more delegation, allowing my team to grow in their leadership skills and to create a sense of purpose, a supportive environment, and open communication.”Susan Hendricks reflected, “My mission should be my focus for all I do. Everything else will fall into place if it fits with my values and purpose.”

These insights from the Iota Cohort reveal a deep commitment to community, innovation, resilience, and connection, both within and beyond the field of education. As the Iota Cohort of the Education Leaders Experience continues, its participants are already reshaping the leadership landscape in South Carolina. Through personal growth, professional insight, and deep connection, ELE creates more than leadership development. It is making a leadership movement.

Education Leaders Experience (ELE) is a ten-month community-based outreach program for South Carolina education professionals. The ELE program was created by Colonial Life in 2016 and is administered in partnership with the Center for Educational Partnerships (CEP) at the University of South Carolina with facilitation technical assistance by Verbalizing Visions, LLC.

The Journey to Where I Was Meant to Be: HOME

Have you ever been stuck in a comfortable place, but know in your gut that it’s time for a change? You muster up the courage to take that step and it becomes the most rewarding experience of your life. That’s just what I did.

I previously taught four-year-old kindergarten at Nursery Road Elementary School for nine amazing years. I developed relationships, supported students in their first school experience, coached parents through their “babies” going to school, grew as a teacher, and became a mom. I was content and comfortable. My only complaint was the long commute between school and home. For years, I dismissed that comfortable feeling as confidence and finally knowing what I was doing as a teacher.

But that wasn’t it. I was too comfortable and content — not pushing myself to grow beyond my comfort zone.

I knew I needed to step out of my comfort zone and do what was best for me, my family, and my teaching career. But just because I knew what I needed to do, doesn’t mean the decision was easy. It was hard, stressful, and confusing. It stirred up feelings of anxiousness, self-doubt, and questions of, “What if?” I learned that even though change can be challenging when you follow your heart, it can also be rewarding.

Three years ago, I accepted a job teaching first grade at the school in my community where my children were zoned to attend.

From the moment I walked across the historic wood floors in the main building at Little Mountain Elementary School, I knew I was “home.”

Had I not taken this leap of faith three years ago, leaving a comfortable place, I wouldn’t have learned so many new things about teaching first grade. I wouldn’t have had the experience of helping students become fluent readers, eager to pick up books. I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to teach in the community where I live. The change allowed me to be involved with my students and their families inside and outside the school building. This leap of faith has helped me grow and advocate for myself as a teacher and a student.

I have learned to love teaching at another grade level, in another school and district. Being nominated by my peers as Teacher of the Year shows I am positively impacting the students, teachers, and community. I am investing in the students in my community, and in turn, in my community’s future. And now through this writing, I can share my voice on my journey “home,” to Newberry County School District.

Three years later, it’s hard to imagine teaching or being anywhere else. Working with a team of teachers you love and respect makes it even better! The School District of Newberry is supportive of its teachers and students.

It is rewarding to work for a district that values you.

I have renewed my National Board Certification and completed all required classes for my Doctorate in Curriculum and Instruction from the University of South Carolina. I have been granted permission from the district office to conduct my research for the defense and completion of my dissertation. For the next two years, I will serve on the teacher forum for the district, where I will have the opportunity to share my voice, and the voices of my fellow teachers, with the superintendent and district office staff. I do all of this with the full support of my school district.

Over the past two years, teachers have participated in the creation of the district’s Instructional Delivery Model (IDM) which will be implemented this school year in Newberry County. All staff provided input in the development of this model. It will be used “to promote a common instructional language, promote consistency, and focus on exemplifying and expanding the best practices identified by our teachers.” The district allows teachers to mentor students from a local high school (Mid-Carolina High School) and Newberry College, to come and learn from us, providing an opportunity to showcase our excellent school, district, and the amazing students we teach.

In another example of districtwide collaboration, schools explored and evaluated different reading curricula approved by the state. Each grade level ranked the curriculum on many criteria. Our data was compiled as a school, and the district used this data to make an informed decision on the reading curriculum that our district would use. Having this platform to share our voices made our opinions feel valued. We used a critical eye when evaluating each resource, considering what would best fit the needs of our students.

Though my journey didn’t start at Little Mountain Elementary, I know all my experiences led me here.

My prior experiences shaped me into the teacher I am. I am constantly reminded of why I decided to leave a comfortable place and am rewarded for this decision by the students I teach and the school district I serve. Seeing the small steps my students take toward their educational goals inspires me to keep chasing my dreams. The excitement on their faces when they learn something new or read a chapter book for the first time is beyond satisfying.

While everyone’s journey is different, that feeling of being “home” leaves a lasting impression and impacts the lives you touch.

Jennifer Long is a first-grade teacher at Little Mountain Elementary School in Newberry County. This is her thirteenth year of teaching, and she has taught in Richland 1, Lexington Richland 5, and Newberry County School Districts. She is a proud wife and mother of three children.

Building a Legacy of Community Impact: The Power of Collaboration and Resilience in Rural South Carolina

Despite my adversity as a child growing up in rural South Carolina, I did not let my environment limit me. Instead, I welcomed it as an integral part of my journey.

Looking back, I realize the adversities I faced were not mere obstacles, but sculptors of my experiences, shaping opportunities for myself and the community I now serve.

Public education was my lifeline. Learning the art of advocating for resources inside the system was vital. Though my parents had only an elementary education, they instilled in me the profound value of prioritizing education, often encouraging me with phrases like, “Ponte las pilas,” a common Spanish expression that literally translates to “Put on the batteries!” This idiom was used to motivate me to get energized, focused, and take action. Ultimately, my parents’ seemingly simple saying became the power source of my journey and determination. As a former multi-language learner student, I developed resilience and grit. My love of learning was sparked by passionate, loving, and resilient public educators, to whom I am forever grateful.

Empowerment Through Family and Community-Centered Engagement

Having witnessed firsthand the struggles families face in accessing quality education and resources, the mission of the Carolina Family Engagement Center (CFEC) resonated deeply with my own experiences. Though each family’s journey is unique, when families actively participate in their children’s education, they lay the groundwork for future success. According to the CFEC, over 40 years of research show that increased family engagement correlates with significant improvements in student achievement, behavior, attendance, and graduation rates.

Consequently, partnerships between families, schools, and communities are essential for fostering our future workforce.

An example of a successful bilingual partnership with a community-centered approach was driven by the city of Walhalla’s Depot and Cultural Center which partnered with bilingual community leaders and local civic leaders, Dr. Swanson from the CFEC, and the Tri-County Technical College (TCTC) executive leadership team. This community-led partnership focused on real and everyday needs. The team designed and created outreach activities and educational events that resonated deeply with the community, ensuring that the college was not only accessible but also reflective of the people it serves. This straightforward, hands-on collaboration led to a historic and substantial increase in Hispanic/Latino student enrollment, with a 40% rise from the summer of 2021 to the summer of 2022, and continued growth into 2023.

Becoming a Community Scientist and Strategic Planning for Rural Advancement

As a science major, I once aimed for a career in the medical field. Instead, my experiences redirected my path to become a catalyst for community change, mirroring how scientists use catalysts to drive breakthroughs. In 2023, I founded the Community Impact Advocacy Network, assembling a multidisciplinary team with diverse socioeconomic and educational backgrounds to launch an effective community impact strategy.

The formation of the Community Impact Advocacy Network sparked the exchange of thought-provoking ideas among expert community members. We secured a time and location for monthly “lab” meetings, where we became increasingly aware of the challenges our rural community faces. Listening directly to medical experts, small business owners, public educators, faith-based organizations, family engagement leaders, and social workers highlighted the need to invest in creative and innovative workforce development partnerships within rural infrastructure. By aligning efforts with key stakeholders, we are developing targeted, actionable strategies that address critical gaps in rural workforce development, ensuring that resources are effectively utilized for maximum impact.

The solution lies in investing and fostering economic and community advancement in the bilingual community health worker pipeline.

Strategic and comprehensive planning is critical, and in some cases, mandated by law. Investing in rural communities to bridge the gap in resources where needs continue to grow is crucial. Current actions and decisions shape future generations’ health and educational landscape. Community Health Workers (CHWs) are essential public health professionals recognized by the US Department of Labor. A significant part of building this infrastructure involves raising awareness, tackling issues with innovative and creative ideas, and understanding that there is a return on investment (ROI) for the business community, which results in a social return on investment (SROI) for all.

Building Bridges, Shaping Futures: Act Now for Rural Health and Education

To support rural families and improve early childhood education, we must prioritize infrastructure investment now. The growing need to connect resources in rural communities demands sustainable financial support that balances healthcare with broader community development. By integrating Bilingual Community Health Workers into our systems, we can effectively address critical gaps in healthcare and education, ensuring families receive culturally sensitive and comprehensive care. Despite their pivotal role, BCHWs remain underrecognized; investing in their work is essential for promoting health and education equity, enhancing workforce capacity, and strengthening our communities.

We need education advocates and community leaders to lend their voices through letters of support and financial contributions to bridge the gap and create a lasting impact. To learn more about how you can partner with us in these efforts, please contact me at: Sarai@communitycatalystshub.com, Sarai@thenolanetwork.org, or via phone at (864) 482-1980.

Sarai Melendez, founder of the Community Impact Advocacy Network, is a dedicated community leader and catalyst for change. With a Bachelor’s in Human Services from Anderson University and advanced training from the University of South Carolina’s Community Health Worker Institute, Sarai is deeply committed to transforming communities through her work as a Certified Independent Community Health Worker (CCHW). Certified by the South Carolina Community Health Worker Association, she has built a reputation for her ability to foster collaboration and drive impactful change.

As a Resource Navigator and Ecosystem Builder, Sarai empowers individuals and families to access essential services, navigate complex systems, and connect with the tools they need for success. Her approach prioritizes tailored support and partnerships to build healthier, more resilient communities. She works to create sustainable solutions for underserved populations through advocacy and relationship-building.

Recognized for her contributions to the community, Sarai was named one of Oconee County’s Top 20 under 40 in 2019. She received the Supporting Staff of the Year award at James M. Brown Elementary School in 2021.

The Lesson I Almost Missed: What One Conference Taught Me About Networking

In 1994, at 28 years old, I became the youngest high school assistant principal in South Carolina, serving at the state’s third-largest high school. Life was a whirlwind. I was married, raising a two-year-old, managing a full social and church life, and working toward my Ph.D., which meant commuting an hour and a half to and from campus weekly after working all day.. The pace was relentless, and exhaustion was a constant companion.

As part of a graduate class in personnel at the University of South Carolina, we were required to attend a conference for personnel administrators in Greenville. I was diligent. I attended every session, took detailed notes, and absorbed as much as possible. At the end of the first day, a reception was scheduled. It was a typical part of conference culture, but it felt like an optional social gathering filled with small talk and drinks. I was exhausted. Instead of attending, I ordered room service and enjoyed the rare quiet of my hotel room. It was a moment of rest that young mothers rarely get.

The next morning, I felt refreshed and ready to learn. As I made my way to the conference rooms, I ran into my professor. We had always shared a good rapport, and I considered her a mentor and even a friend. That morning, however, she did not look pleased.

She pulled me aside and told me, quite bluntly, that I had missed the most important part of the conference: networking. She explained that the education community in South Carolina is like a small town, where relationships are everything. By skipping the reception, I missed a critical opportunity to make connections that could support my career for years.

She did not ask why I had chosen not to attend. She did not know I was tired to the bone or that I simply needed space. Her words stung. I wanted to defend myself. I wanted to explain that I had not been out partying or avoiding responsibility. I had just needed rest. But the reason did not matter. What mattered was the lesson she was trying to teach me.

None of us likes being called out, and I am no exception. But the truth of what she said stayed with me. It reminded me of a quote I once attributed to Maya Angelou. However, I later learned it came from Maimonides, a medieval rabbi and philosopher: “Accept the truth from whoever utters it.” No matter the source, the truth is still the truth.

Thirty years later, I fully understand the value of that lesson. The power of networking has shaped my career. Relationships have introduced me to mentors, opened new opportunities, and helped me step into roles I never imagined. Today, I make it a priority to help others do the same.

Networking is not just about professional advancement. The right connections allow us to do the good work that needs to be done. They help us build authentic partnerships, solve problems, and move ideas forward meaningfully.

We often talk about networking, but what does it look like in practice? Here are a few ways I have seen it come to life.

What Networking Looks Like in Action

In-Person Networking

- Attending Events: Conferences and professional gatherings are great places to introduce yourself, share ideas, and build relationships.

- Casual Conversations: Sometimes, the most valuable connections begin with a spontaneous conversation in an elevator, at a coffee shop, or during a break.

- Following Up: After meeting someone, a short message or email can help sustain the relationship.

Online Networking

- Engaging on LinkedIn: Sharing posts, commenting, and connecting with others in your field keeps you visible and connected.

- Joining Online Groups: Participate in forums, professional Facebook groups, or Slack communities related to your interests and expertise.

- Cold Outreach: Reach out to someone whose work you admire. A thoughtful, personalized message can go a long way.

Giving and Receiving Support

- Offering Value First: Share job leads, introduce colleagues, or provide helpful resources without expecting something in return.

- Asking for Advice: Reach out with genuine questions and a willingness to listen.

- Collaborating: Work with others on projects, share ideas, and build something together.

Workplace Networking

- Cross-Department Relationships: Connect with colleagues outside of your immediate team to broaden your perspective.

- Participating in Socials: Attend work events, happy hours, or team lunches to build rapport in informal settings.

- Seeking Mentorship: Reach out to those whose leadership you admire and ask to learn from their experience.

Networking Through Volunteering and Hobbies

- Joining Professional and Community Organizations: Engage with groups that align with your values and interests.

- Connecting Through Shared Interests: Whether it is a book club, sports league, or service group, relationships built through common interests can lead to professional growth.

The key to all of this is authenticity. Networking should not be transactional. It should be rooted in real relationships, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to growth.

That missed reception in Greenville became one of the most important lessons of my early career. Networking is not just a social activity. It is a professional responsibility and a powerful tool for impact.

And for that lesson, I am forever grateful.

Finding Home in a Village Built for Educators

Turning a vision into reality can often feel like an uphill battle, but through the collective efforts of Dr. J.R. Green, the Fairfield County School District Education Foundation, and a dedicated team of partners, that vision has taken shape in a profound way. With careful planning, persistence, and a shared belief in supporting educators, an idea became something tangible. In August 2024, the first 16 educators of FCSD stepped into a milestone moment—moving into the newly established Village for Educators, a community designed to support those shaping the next generation.

For me, the experience of moving into a brand-new home is both exhilarating and transformative. It’s more than just a change of address—it’s a fresh start, a renewed sense of belonging, and a space to grow. As someone who thrives on community, adaptation, and lifelong learning, I see this transition as an extension of the very principles I teach my students: embrace change, build relationships, and continue learning. Settling into a new home is not just about unpacking boxes—it’s about redefining what it means to live, work, and connect in a place intentionally built for educators.

Inside these walls, my home is a personal sanctuary, a space where I can recharge after long days in the classroom. It’s where I reflect, plan, and find balance between my professional and personal life. Every corner of my house carries possibility—the potential for comfort, creativity, and peace. The ability to shape a space that nurtures both productivity and relaxation is invaluable, especially in a career as demanding as teaching. Coming home to a place that feels truly mine enhances my well-being and allows me to be fully present for my students each day.

Beyond the walls of my home lies something just as powerful—a community of educators walking the same journey. In this village, I am surrounded by peers who understand the long hours, the triumphs and struggles, and the deep commitment it takes to be an educator. This shared experience fosters a sense of connection that extends beyond our classrooms and into our daily lives. Whether it’s gathering for neighborhood meetings, collaborating on new teaching strategies over coffee, or simply sharing words of encouragement at the end of a tough day, the relationships built here are a testament to the power of community.

Of course, any transition comes with its challenges—adjusting to a new space, building new routines, and learning the rhythms of a new neighborhood. With those challenges come even greater rewards: a renewed sense of purpose, an opportunity for growth, and the chance to be part of something bigger than myself. Just as I guide my students to embrace change with curiosity and resilience, I remind myself to do the same.

Living in the Village for Educators is more than just having a place to call home—it’s about being part of a movement that values, supports, and uplifts teachers. It’s about reimagining what it means to live and work in a community that understands the heart of education. And, like every journey in learning, this is just the beginning.

Dr. Rolando Curabo is the STEM Lead Teacher at Fairfield Middle School with 27 years in education, including experience as a principal. He spent 11 years teaching high school and college in the Philippines before moving to the U.S., where he has taught middle school for 16 years. A Teacher of the Year (2021-2022) honoree, he has also led the Science Department for eight years. Dr. Curabo holds a PhD in Educational Management and is currently pursuing another in Science Education. This story is made possible by the Center for Educational Partnerships.

Coding a New Path: How Teaching Brought Me Home

Career transitions are never easy, especially when leaving a stable, well-paying field for something completely different. My journey from computer science to early childhood education was filled with uncertainty, challenges, and moments of doubt. Ultimately, it led me exactly where I was meant to be—back home in Fairfield County, teaching in my community and living among fellow educators who understand the joys and struggles of this profession.

I began my career in computer science, drawn to the logic and problem-solving aspects of the field. I loved the structure, the challenge of writing clean, efficient code, and the sense of accomplishment when a program ran flawlessly. But over time, something felt missing.

My work, while intellectually stimulating, lacked a personal connection. I wanted to do something directly impacting people’s lives and feel meaningful beyond a screen. That’s when I started considering teaching.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that education was calling me in a way that technology never had.

So, I took a leap of faith and returned to school, earning my Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT) in Early Childhood Education. With my MAT in hand, I was eager to start my teaching career. I began working in the Head Start program, first in Charleston County and then in Berkeley County, South Carolina. I was excited and optimistic, ready to bring energy and passion into the classroom. However, the reality of the job quickly set in. Teaching in Head Start was overwhelming. The demands were intense—not just academically but socially and emotionally. Many of my students came from difficult home situations, and I found myself navigating a complex web of social services, behavioral challenges, and administrative requirements. I loved my students but felt disconnected from the joy of teaching. Instead of feeling fulfilled, I questioned whether I had made a mistake. Had I left one career I didn’t love, only to step into another that wasn’t the right fit either?

After a few difficult years, I returned to my hometown in Fairfield County. It was a homecoming in more ways than one—physically, emotionally, and professionally. I felt something different when I stepped into my new classroom. For the first time, I truly belonged. The school welcomed me with open arms, and the sense of community was immediate.

I wasn’t just another teacher—I was someone returning to give back to the place that had shaped me.

What made this transition even more special was discovering a community of fellow educators who lived and worked alongside me. Many of my neighbors were teachers—people who understood the exhaustion, the long nights of grading, and the emotional investment that comes with shaping young minds.

The mornings in my neighborhood began with familiar sounds—teachers loading their bags into cars, the hum of school buses, and waves exchanged between colleagues heading to their respective schools. In the afternoons, you might see a group of us unwinding at a local coffee shop, discussing ways to engage students, or sharing a laugh about the funny things kids say. Outside school, I ran into students and their families at the grocery store, the park, and community events.

While teaching never truly stops, it no longer feels like a burden. Instead, it feels like being part of something bigger—a network of educators and families all working together to shape the next generation.

After six years of teaching, I made another major transition—moving into the Teacher Village, a community designed specifically for educators in Fairfield County. The most immediate benefit was the drastic reduction in my commute. My hour-long drive shrank to five minutes, gifting me back time and energy I didn’t realize I was missing. With those extra moments, I could start my mornings without the stress of traffic and return home with the capacity to plan lessons, pursue professional development, or simply recharge. But beyond convenience, living in a community made up entirely of educators has been an experience like no other.

There’s an unspoken understanding among us—we all know the demands of the job, the long hours, and the emotional investment it requires. I don’t have to look far if I need help brainstorming a lesson idea or venting about a tough day.

The atmosphere here is different from any other neighborhood I’ve lived in. Instead of small talk about the weather, our conversations naturally turn to classroom successes, new teaching strategies, or ways to support our students better. There’s a shared sense of purpose—everyone here is committed to education, and that energy is contagious.

Living in the Teacher Village has made teaching feel less isolating. I feel more supported, inspired, and connected to the larger mission of education.

It’s a place where work and home blend seamlessly—not in a way that overwhelms but in a way that reinforces the passion we all have for our students.

Looking back, I don’t regret my time in computer science or my early struggles in education. Every step of my journey has taught me something valuable. My tech background gave me problem-solving skills that I use daily in the classroom—my challenging years in Head Start taught me resilience and patience. My return to Fairfield County has shown me the power of community, support, and finding the right environment to thrive. Now, I wake up excited to go to work. I see my students growing, learning, and discovering their strengths. I see familiar faces at school, in my neighborhood, and all around town, reinforcing my deep connection to this place.

Sometimes, life has a way of bringing us full circle. I found purpose right where I started—back home.

Shequila Davis, a third-grade teacher in Fairfield County School District and a resident of the Teacher Village—an initiative supported by the Fairfield County Education Foundation—shares her journey in this field narrative. This story is made possible by the Center for Educational Partnerships.

More Than a Classroom: How Education Led Me to Build a Village

Teaching has been at the heart of my life for over fifty years. From my early days as a special education teacher in Pennsylvania to my time as a professor at Winthrop University in Rock Hill, South Carolina, my passion has always been rooted in identifying student needs and finding ways to meet them.

Growing up in a military family, I experienced firsthand the challenges of an inconsistent education. In the 1950s, schools near the Norfolk Naval Base were overcrowded, and I attended school for only three hours a day. When my family moved to Pennsylvania, I found myself academically behind and struggling to adjust. To make matters worse, my teacher forced me to write with my non-dominant hand, making me feel even more out of place. I hated school. I felt stupid. But my mother refused to let me fall through the cracks—she tutored me daily, pushing me to catch up and believe in myself. Looking back, I now see how that experience shaped my path into special education. I understood what it felt like to need a teacher who truly saw you, who believed in your potential even when you doubted yourself.

That sense of purpose carried me through seven years of teaching special education in public schools, then through my doctoral studies at the University of South Carolina, and finally into a long and fulfilling career at Winthrop University. There, I didn’t just teach future educators—I built programs that connected students, teachers, and communities meaningfully.

One of those initiatives, Phone Friend, provided an after-school talk line for elementary students across York County. For seventeen years, my special education majors answered calls from children—many of them latchkey kids—who just needed someone to listen. Another program, WINGS (Winthrop’s Involvement in Nurturing and Graduating Students), paired middle school boys with Winthrop student mentors, creating bonds long after the program ended. Some of those young men still meet up today, reminiscing about the friendships and guidance that shaped them. And then there was the traveling puppet show, where our college students introduced young children to characters with disabilities, teaching lessons about inclusion in ways only storytelling can.

One of those initiatives, Phone Friend, provided an after-school talk line for elementary students across York County. For seventeen years, my special education majors answered calls from children—many of them latchkey kids—who just needed someone to listen. Another program, WINGS (Winthrop’s Involvement in Nurturing and Graduating Students), paired middle school boys with Winthrop student mentors, creating bonds long after the program ended. Some of those young men still meet up today, reminiscing about the friendships and guidance that shaped them. And then there was the traveling puppet show, where our college students introduced young children to characters with disabilities, teaching lessons about inclusion in ways only storytelling can.

I retired after thirty years at Winthrop—but I wasn’t done. I served twelve years on the university’s Board of Trustees and later worked alongside my husband, Jim Rex, during his time as South Carolina’s State Superintendent of Education. Then, I found myself drawn to Fairfield County, where I co-founded the Fairfield County School District Education Foundation with one goal: addressing the recruitment and retention of teachers in our rural district.

That’s when I took the biggest leap of my career—not in a classroom or university, but in housing development.

With a land gift from the school district and critical financial support, we spent eight years building the first residential community for teachers in South Carolina. What started as an idea has grown into something real: 16 homes for teachers, plus one for University of South Carolina education majors completing their senior year internship in a rural school. And by summer 2025, we’ll have 9 more homes, thanks to generous contributions from United Way of the Midlands, the Central Carolina Community Foundation, and TruVista Corporation.

With a land gift from the school district and critical financial support, we spent eight years building the first residential community for teachers in South Carolina. What started as an idea has grown into something real: 16 homes for teachers, plus one for University of South Carolina education majors completing their senior year internship in a rural school. And by summer 2025, we’ll have 9 more homes, thanks to generous contributions from United Way of the Midlands, the Central Carolina Community Foundation, and TruVista Corporation.

I never expected to become a housing developer. But life has a way of taking you exactly where you’re meant to be.

At every stage of my career, I have been surrounded by passionate, dedicated people who believe in the power of caring, connecting, and creating something new where it’s needed most. Whether it was helping a struggling child find their confidence, mentoring future educators, or now, providing teachers with a place to call home, the work has always been about the same thing—building something that lasts.

Creating new solutions to persistent problems is incredibly fulfilling – and with any luck, I’m far from finished.

Sue Rex, a lifelong educator and advocate for teacher support, has dedicated her career to special education, teacher preparation, and innovative community initiatives. As co-founder of the Fairfield County School District Education Foundation, she was pivotal in creating South Carolina’s first residential community for teachers. In this field narrative, she shares her journey from the classroom to building a home for educators. This story is made possible by the Center for Educational Partnerships.

Right on Time

It is too good to be true. How many times have you thought of those words? With each passing day, excitement mixed with a nagging sense of uncertainty. I had worked so hard to reach this point, but as I stood on the brink of my college graduation, I still felt unsure about the future. While my family was incredibly supportive, I wasn’t worried about where I would end up teaching. I was just grateful to be the first person in my family to earn a college degree. I knew how much this moment meant to me and my family, who had sacrificed so much to support me. I would have been thankful for any school that offered me a chance to teach.

But as graduation day approached, my worries shifted. I thought less about the degree I had worked so hard for and more about where I would live. I had never lived on campus during college, always staying with my family in Columbia, South Carolina. But now, as a new graduate, it was time to think about how to support myself—and more importantly, how to support my family stably. The weight of that responsibility began to feel overwhelming, especially with the challenges ahead.

Then things became even more complicated. My aunt, who was also my landlord, had fallen ill and made the difficult decision to sell the home we had lived in for the past fifteen years. I couldn’t fully process it at first. The house that had been our family’s safe haven, where we had made so many memories, was about to be sold. My emotions were torn. Should I celebrate the fact that I was about to graduate with a degree in hand? Or should I comfort my parents as we faced the looming uncertainty of not having a place to call home?

When I thought things couldn’t get worse, an unexpected ray of hope appeared. The day before my graduation, I received a message from my university. At first, I could hardly believe what I was reading. It was an email inviting me to join a unique opportunity for soon-to-be teachers. It was like something out of a dream. The message described a chance to live in a brand-new, two-story home within a special community designed just for teachers—the Village in Winnsboro in Fairfield County. Not only would I live rent-free for a year, but I would also live in a community of educators. It was an opportunity that seemed like it couldn’t possibly be real, but there it was.

The offer was exclusive to graduates from the College of Education beginning their teaching careers in Fall 2024. With my family facing a housing crisis, I couldn’t help but wonder, could this teacher village be real? Could this be the answer to the challenges we were facing? Was this too good to be true? The idea of living in a community of educators—people who truly understood the work and its challenges—felt almost surreal.

After discussing it with my family and now-wife, I decided this was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up. I was going to move to a place I had never been, to a town I didn’t know, to start a career in a field I was passionate about. Though the uncertainty of the move weighed heavily on me, I had a deep sense of trust that this could be the fresh start I needed. I believed in the potential of this opportunity.

Thankfully, my family’s housing crisis was eventually resolved after my graduation. So, upon my arrival in the Village in Winnsboro, that weight of responsibility fell off my shoulders. I was welcomed by a warm, tight-knit community of educators who immediately offered their support. There was a sense of unity in the air, a feeling that we were all together, facing the same challenges, and lifting each other. The teachers and staff in the school district made it clear that they were invested in my success. I felt embraced by the very community I had been introduced to—a sense of belonging I hadn’t expected so soon.

Teaching in Fairfield County has turned out to be an incredibly fulfilling experience. The journey has been challenging as a first-year teacher, but Fairfield County School District has provided me with the tools and support I need to grow and succeed. I have a fantastic reading coach, a dedicated teaching coach, and a mentor who helped me navigate the first few months of teaching. With a student-teacher ratio of just 15:1, I can form meaningful relationships with each student, allowing me to tailor my instruction to meet their needs. The community, especially at the district office, has been welcoming. Everyone knows me by name, even the superintendent. That’s not something I could have ever expected in a larger district.

Being in a rural area, it didn’t take long for me to understand the depth of connection between the schools and the surrounding communities. People genuinely care about one another here. Teaching in Fairfield has given me a greater sense of purpose, knowing I am part of something genuinely making a difference.

Teaching in Fairfield feels like a calling—a daily commitment to shaping young minds and providing them with the tools they need to succeed. I can’t speak for all the teachers in the district, but my school’s culture is deeply rooted in family and a shared passion for education. Many of my students are relatives of other families who have attended this school for generations. Their parents and even their grandparents walked these same halls. It’s a place where education is more than just a job—it’s a legacy passed down through the years.

At my school, we strive for excellence in every way. Fairfield County places a high value on using best practices in education. From implementing structured literacy to incorporating the latest technologies, like artificial intelligence, into the classroom, the district ensures that students and teachers stay ahead of the curve. Accountability is a key part of the culture. We work tirelessly to meet school-wide goals, and our administrators hold us to high standards, ensuring that we are consistently striving for excellence. I feel fortunate to work alongside such dedicated colleagues; their commitment pushes me to give my best every day.

But what truly sets Fairfield apart is the sense of belonging. I moved here as an intern from an urban area, and I’ve experienced the difference firsthand. The most significant change I’ve felt in Fairfield is that I am not just a number here. The district truly values its educators. As a result, they offer one of the state’s highest teacher retention bonuses, reflecting their recognition of the importance of retaining high-quality teachers. Realizing how crucial recruiting and retaining skilled educators is, the district invested in creating a visionary project—a community of educators like no other. After years of planning, the Village in Winnsboro became a reality in Fall 2024. This innovative community symbolizes the district’s commitment to its teachers.

“Home” in the Teacher Village means much more than just a roof over our heads. It’s about the community we’ve built together. Living in a neighborhood of fellow educators is unique, but having the opportunity to share our lives as professionals and friends makes it even more special. We talk about our students, challenges, and victories—but we also make time to relax, have fun, and enjoy each other’s company. Whether walking through the streets, playing games in the neighborhood, or just having casual conversations, the bonds we’ve formed here make the Village feel like a second family.

Living in the Village has deepened my appreciation for my profession in ways I never imagined. Fairfield County’s commitment to investing in its educators shows how much they value us. I wake up every morning grateful for the opportunity to work in such a supportive environment. With fewer financial worries, I can pour all my energy into teaching my students and improving as an educator. The Village in Winnsboro has not only provided me with a place to live—it has given me a sense of purpose, belonging, and pride that has made me even more determined to make a difference in the lives of my students.

Rooted in Education: Building a Life Where I Teach

Some of the most important lessons aren’t taught in a classroom. They happen in the quiet moments before the first bell, in conversations on the sidelines of a soccer match, in the simple act of showing up—day after day. Teaching isn’t just about delivering content; it’s about being present, trusted, and part of something bigger than yourself.

After 25 years in education, with the last 10 years in Fairfield County School District, I’ve understood that teaching is more than instruction—it’s about the connections we build, the communities we serve, and the stability we create for ourselves and our students. My work in the Multilingual Learner Program and as a soccer coach at Fairfield Central High School has given me a front-row seat to the power of investing in educators. But beyond that, Fairfield is where I’ve built my home—not just as a teacher, but as a husband, father, and member of a close-knit community.

Teaching in Fairfield isn’t just a job—it’s a commitment to the students and families who trust us to guide them. In a rural district like ours, relationships matter. I don’t just see my students in the classroom; I see them at the grocery store, church, and soccer field. That constant presence creates a deeper level of accountability, investment, and trust. As a multilingual learner educator, I travel between schools, working with students from kindergarten to high school, helping them navigate academics, language barriers, and the challenges of adjusting to new environments. Teaching here is more than just delivering content—it’s about mentorship, advocacy, and ensuring every student feels seen and supported. I work closely with teachers, counselors, and social workers to ensure our students have what they need inside and outside the classroom. That kind of collaborative, student-centered approach is what makes this district special.

But connection alone isn’t enough to keep teachers here. Too often, rural districts like ours lose great educators because of long commutes, limited housing options, or the difficulty of balancing work and home life. That’s why the Teacher Village isn’t just a housing development—it’s a lifeline for those who want to build careers and communities in the same place. It removes barriers and gives teachers a reason to stay.

For me, moving into the Teacher Village has been a game-changer. It’s not just about the shorter commute, though that’s part of it. What truly makes a difference is how much easier it is to balance work and home life. With my new home just minutes from school, I’ve found more time to engage with my students, reconnect with my family, and recharge after a long day. I no longer rush to beat traffic, and my kids feel safe here and know I’m always close by. There’s something powerful about that sense of security—for them and for me. This place isn’t just convenient—it’s a foundation that allows me to be the best version of myself, both in and out of the classroom.

Beyond the personal benefits, living in the Teacher Village has strengthened my connection to my students and their families. I can attend more school events, visit students’ homes when needed, and engage with the community in ways that wouldn’t be possible if I lived farther away. Proximity matters, and having a community of fellow educators next door fosters a shared sense of purpose and support. The thoughtful design, affordability, and accessibility of these homes show that Fairfield County values its teachers—not just for the work we do, but for the lives we build here. When a district invests in its educators, the entire community benefits.

The Teacher Village is more than just a place to live—it’s a national model for how we support and retain teachers in rural districts. It’s proof that when you remove barriers like long commutes and high housing costs, teachers not only stay but thrive. Fairfield isn’t just where I work—it’s where I’ve built my home, career, and future. By creating a stable, supportive environment for educators, the district isn’t just keeping teachers—it’s strengthening schools, improving student outcomes, and building a community where everyone can succeed.

Fairfield isn’t just where I work—it’s where I show up, invest, and stay. And that’s exactly the kind of place I want to call home.

I’m Victor Hernandez, a multilingual learner educator and head soccer coach with the Fairfield School District in Winnsboro, SC. I’m passionate about mentoring students both in the classroom and on the field.

Parents and Teachers: The Joy of Family Engagement

I was shocked to learn that Ms. G. sent the first LinkedIn connection request of any of my parent/teacher relationships and surprised she took the initiative to communicate with me. Her son, T., was beginning his senior year of high school. I will always remember her as an involved parent with high expectations for her son, and her approach to motherhood taught me the significance of the saying, “It takes a village to raise a child.”

I met Ms. G. three years ago at her son’s 9th grade Individualized Education Program (IEP) meeting. While she was attentive to my proposal for her son’s educational plan for the year, she had goals of her own for him, and she made it clear that she did not like the recommendations I proposed. I suggested that T.’s annual goals shift to focusing more on the skills he needed to reach his postsecondary aspiration of becoming a truck driver. Ms. G. simply stated, “This is unacceptable to me. He is in ninth grade, and he should be reading on a ninth-grade level before we focus on anything else.” My attempts to help shift Ms. G’s focus towards preparing T. for his goal of becoming a truck driver were unsuccessful.

The differing roles between a teacher and a parent were clearer than ever. We both supported T.’s future goal of becoming a truck driver, however, as a supportive teacher with a different perspective, my suggestion included using T.’s interest in truck driving to improve his reading abilities. Helping T. required me to teach his family the significance of his independence.

Although we are more commonly known for our work with students, teachers help guide families through the transition of releasing parental guidance to independence.

T. was a student in my unique ninth grade academic support class. There were several students in the class whose mothers had passed away, including sisters who lost their mom two weeks before starting the school year. I connected with the Carolina Family Engagement Center and committed to conducting research on positively influencing parent engagement in student career planning. Despite disagreements, parents like Ms. G. participated in activities which helped make my initiatives successful. My students were motivated to succeed because they had their parents’ support and attention. While I am grateful for the opportunity to impact my students’ success, I’m curious about having a greater impact if given the opportunity to guide students at a younger age. Realizing the opportunity to support young students’ career interests through adolescence is a rewarding journey in teaching and parenting.

Overall, my commitment to the Carolina Family Engagement Center led to more positive communications with parents about their child’s goals, and students were more focused on their academic performance.

My conversations with students and families helped me assess the amount of family time, parental knowledge, and level of independence within each of the families I served. While some of the parents accepted my feedback, I realized that conversations with parents, like Ms. G., were productive for both students and families. As a parent, asking my daughter’s teacher questions about her feedback, while uncomfortable, allowed us to have mutual understanding and develop common goals. The same was true for my relationship with Ms. G., and it was clear she knew T. well, but my communication with her seemed to cause conflict between her and T. at home.

While my class had many discussions with T. about the powerful, positive impact and influence of engaged parents, he did not agree that his mom’s involvement helped him in any way. However, being a mother gave me the opportunity to understand the challenges of parenting, and the difficult balance required in teaching independence.

Although I was a fairly new mom, my daughter and I shared so many pivotal experiences in her first six years of life. Among other events, her tumultuous birth involved life-threatening moments for both of us, including my having a stroke. As a result, I understood what it felt like to have a disability, have your independence stripped due to a disability, care for someone with a disability, and feel disappointment when you expected to be celebrating.

T.’s family was avoiding the inevitable turning point in parenting: teaching independence. Teaching independence is a very difficult transition when a parent doesn’t allow a child to fail. Therefore, my response to our parent-teacher conflict was guided by my belief that there are many lessons learned directly and indirectly through all life experiences. Ultimately, it is challenging situations that shape people into becoming wiser. Ms. G. needed time to adjust and to accept the reality that T. was growing up, and he wasn’t going to achieve everything she wanted him to on her schedule.

While Ms. G and I never came to complete agreement, we maintained mutual respect for our unique perspectives, our parent-teacher relationship, and our dedication to T.

By the end of that school year, I reached the conclusion that schools consist of public servants. Public servants, driven by awareness and respect, are a part of the village that every parent hopes to build for their families. Although the year started with my overzealous approach to supporting my daughter through first grade, I soon realized that parents’ influence is limited. Ultimately, teachers hoping to make an impact, like my daughter’s teacher and myself, become a part of the child’s village.

Accepting Ms. G.’s LinkedIn request confirmed she learned the significance of independence and the meaning of “a village.” I thanked her for reaching out to me and wished her and T. well in his senior year of high school. Ms. G. replied, “Yes ma’am. It is a long road, but he is slowly getting back on track. Thank you for everything that you have done. It’s truly appreciated.” Her gratitude was a warm confirmation which taught me that many people contribute to a child’s development and celebrate their success.

Being a part of a village is not limited to teachers, it involves everyone fulfilling their purpose and role. Since we all have a purpose, it is imperative to your village and yourself that you fulfill it.

Dr. Robyn Mixon is a South Carolina native and a Charleston County School District graduate. She resides in Summerville, SC, and currently serves as a Transition Specialist in Dorchester 4 School District. She has worked as a special education educator for the past 20 years, supporting students with various disabilities. Dr. Mixon is strongly committed to impacting students through family engagement.