Reality Check: Preparing for Life Beyond School Through Strong Community Partnerships

In my professional role, I enjoy working with parents and caregivers within and outside of schools. Recently, a parent completed the Parent Leadership Partner (PLP) Program through the Carolina Family Engagement Center (CFEC). This year-long program, followed by a certificate of completion and graduation ceremony, allowed 15 parents to meet monthly to complete coursework designed to help parents better navigate the public education system. The program allows them to see themselves as advocates and leaders through the process. This particular parent, Randall Lowder, was empowered to become the chair of the School Improvement Council at his son’s junior high school and initiated the following call to action for a “reality check” event at his son’s middle school.

There’s education, and then there’s education. Randall Lowder was concerned about the education required for handling life in the real world beyond book reports and lab experiments. How could his son and other students learn about money management, paying for housing, budgeting for medical bills, car insurance, and future family needs?

Those lessons weren’t taught at Manning Junior High School, where Lowder was chair of the School Improvement Council (SIC). Lowder, a single parent, discussed his worries with me. As part of my CFEC Family Engagement Liaison job, I attended SIC meetings during CFEC’s four-year partnership with Manning Junior High. Often, CFEC liaisons help schools in important ways beyond academics and other school goals. As a fellow single parent, I understood his concerns.

So was born the Reality Check Expo, an event that supported the school’s 180 eighth graders to start thinking about their futures in practical terms. Another unexpected benefit: firmer ties to the community, thanks to the participation of local businesses.

“Parent and community involvement has always been a struggle with students at this age level,” Principal Terrie T. Ard shared. “The Reality Check Expo allows our school to work with parents and community stakeholders, such as the chamber of commerce, to help host such an event for our students.”

At the expo, students visited various booths in the school gym to learn about money management. Based on their career interests and hypothetical future family size, each student visited different experts to see what income they needed to pay for their ideal way of living. Housing, insurance, utilities, groceries, entertainment, clothing, medical, and childcare experts guided them at individual booths. Outside, different booths were set up for students to get a sense of various vehicle costs and other means of transportation. The last booth was a bank booth, where a banker tallied each student’s financial status and guided them through applying for a loan if they needed more money. Students also met with individual teachers to discuss job and career options and post-secondary education requirements based on their interests.

The pilot Reality Check Expo was so successful that future expos were planned to include students in sixth and seventh grades. Expo planners based this event on a successful program model in Yukon Public Schools in Oklahoma, which started its Reality Check event in 2002. Lowder learned about the program through social media and contacted the school for information. Educators shared their materials with the Manning Junior High SIC and other schools nationwide.

As a Columbia resident and non-member but regular attendee of the Manning Junior High SIC, I served as a helpful observer rather than an emotionally involved participant. This neutral role allowed me to smooth tensions between two members of the SIC. When one party approached me asking for advice about how to diffuse the situation, I could respond in a way that mediated the situation. I kept a calm spirit and did more listening than talking to identify issues and propose solutions. I advised how to handle the problem, and both voices were heard.

The tension abated, and the Reality Check Expo moved from idea to reality. Principal Ard appreciated the outcome, recalling, “Our CFEC liaison has been a tremendous asset to our school. Having someone to bridge the divide of parent and school relations has been a positive experience.”

I believe in schools keeping open communication with the community they serve. Often, CFEC liaisons help schools in important ways beyond academics and other school goals. My work as a CFEC liaison at Manning Junior High School to find resources to support schools and families paid off: five book vending machines and three CFEC Community Family Resource Centers (CFRCs) were placed in Clarendon County. CFRCs are high-quality stations providing free community and school materials and information, some translated into Spanish.

Ard, who notes her school’s 2022 “excellent” rating in the South Carolina Department of Education report card, affirms MJHS’s positive experience with CFEC. “The entire process has been great,” she says. “I feel our family-school-community engagement grew stronger every year of the partnership. With Ms. Outing’s help, I feel the line of communication with parents, community, and school has strengthened.”

There is this notion that many parents don’t care or believe it is entirely up to educators to ensure their children are prepared for life beyond school. Often, barriers such as work, transportation, homelessness, hunger, abusive relationships, negative past experiences, and lack of knowledge are overlooked. Over the past several years working as a CFEC Family Engagement Liaison in the SC Pee Dee region, I’ve had the opportunity to see otherwise.

What began as one parent’s idea, inspired by a different school district’s implementation in another part of the country, ended with much more than anyone could have hoped. This collaboration among community partners and middle school educators, parents, and students offers encouragement and a powerful model for other schools to follow.

Ranina M. Outing, MHA, MPH, is South Carolina’s Pee Dee Regional Family Engagement Liaison at the Carolina Family Engagement Center, funded by the U.S. Department of Education (grant award #s U310A180058 and S310A230032) and housed at the University of South Carolina’s School Improvement Council in the College of Education. Outing has served in this position for five years and has extensive experience in administration, providing training, technical assistance, and coordinating programs. She earned a B.S. degree in Business Management with a Master of Business in Healthcare Administration and a Master of Public Health with a focus on improving the life and well-being of individuals through a combination of analysis, psychology, social work, and methodologies. She sincerely thanks Aida Rogers, CFEC’s Marketing and Communications Coordinator, who contributed to this story.

Sometimes the Grass is Greener

It is common for people to move from job to job, attempting to find something “better.” Sometimes, this leads to disappointment when it’s discovered that the grass isn’t always greener on the other side. However, in my experience, changing school districts proved to be the greener grass opportunity I needed to thrive.

I began teaching in 2015 and faced numerous challenges in my initial district and school. Despite difficulties, those three years were a period of significant personal and professional growth. I gained many friends and colleagues who helped me become the teacher I am today. Our placements in life serve a purpose, and I have no regrets about where I started my career.

But after three years, I knew I wanted to find a place where I felt supported and heard.

Change and discomfort are not natural allies of mine, but I took a leap of faith and applied for a Montessori teaching position within the School District of Newberry County.

My first interview was for an upper elementary Montessori position. Fate intervened when that position was filled, leading me to interview at Boundary Street Elementary School for a lower elementary Montessori position. Auspiciously, the teacher who filled the position at the first school I interviewed with was the teacher who left Boundary Street Elementary. I accepted the 2018-2019 position with excitement and anticipation.

Everything happens for a reason, and I immediately felt welcomed and at home.

Newberry School District’s motto is, “One District, One Team, One Mission,” this statement accurately depicts the collaborative, helpful, community-based district that’s been my professional home for the past six years.

Boundary is also a significant reason why I feel like I belong. The administration strongly supports teachers and staff, my colleagues are collaborative, and parents are involved. Together, we embody the “One Team” mentality and are dedicated to meeting students where they are, guiding them to excel, and ensuring they feel loved and valued.

As someone who grew up in an environment where I did not feel loved or valued, I wanted to work where staff make sure every child who walks through the door knows they are loved and that they matter. No child should ever go a day feeling unworthy, unloved, or unnoticed. Our school’s motto is “Be You. You Matter. And You Are Loved.” The students are our WHY.

I consider myself extremely fortunate to teach my students for three years at a time. This allows me to form meaningful relationships with families, teach siblings, and engage actively in their lives within the Newberry community, both in and out of school. This connection reinforces my sense of belonging, making me feel like a valued part of the community despite not residing in Newberry County.

Beyond fostering a sense of belonging, Newberry has provided me with countless opportunities to enhance my own and my students’ skills. Through LETRS training, an ML endorsement, and attending reading and Montessori conferences—all fully supported by the district—I have been able to embody the lifelong learning mindset I strive to model for students.

Aside from providing growth opportunities, the district office staff actively engages with campus staff. They ask, listen, and value teachers’ voices and input. They also offer constructive feedback and words of encouragement. Recently, our Assistant Director of Curriculum and Director of Elementary Education visited my classroom and shared positive feedback. One note mentioned, “I enjoyed visiting your class. Expectations have been established along with procedures.” Their presence and acknowledgment of our work are impactful, validating and reinforcing that our efforts are making a difference and are noticed.

Amazing and loving educators who leave the profession often do so because of school and/or district culture and climate issues. According to SC – Teacher Top Ten Findings, “School-level factors, like issues with student discipline and lack of administrative support, contributed the most to teachers’ decisions to depart.” We need support and guidance when challenges arise, not to be pushed aside and unheard.

Conversely, a supportive district and school-level administration that truly listens can significantly influence teacher retention.

“Admin support and influence over school policy had the strongest relationships with teacher job satisfaction and intention to stay in the profession.” According to the SC School Report Cards, Newberry boasts a 97.2% teacher retention rate. This is comparable to the 97.9% state average. In addition, out of 390 teachers who completed the opinion survey last year, 91.6% of teachers were satisfied with the learning environment. This is slightly higher than the state average of 90.7%. There is a direct correlation between the climate of the district, the school where teachers work, and their decision to stay in the classroom.

Encouraging teachers to have a voice and influence in district and school policies can also prompt educators to stay in the profession. For example, last year I had opportunities to share my ideas and work within my school. Our school’s leadership team worked together to find solutions to problems and implement new ideas to impact the community positively. I led the Student Recognition Committee and created a way to showcase our students. When I was completing the National Board process, I shared a presentation on Question Answer Relationships (QAR) in faculty meetings. This instructional approach improved our students’ comprehension and fostered stronger test-taking skills by encouraging them to think critically beyond the text. My instructional coach also shared this work with other instructional coaches across the district. This underscores how our district supports and values teacher influence and input.

The support of the district, my school, and the community has shaped me as a teacher. Because of this support, I was recognized as my school’s 2024-2025 Teacher of the Year. To be recognized for this honor by my colleagues means the world to me. This opportunity also enables me to represent my colleagues as part of the teacher forum for our district. It allows me to listen, advocate, and communicate two-way information between the district and our school.

The ongoing challenges of teaching can make our “grass” appear brown and lifeless. Discovering a place where you feel a sense of belonging, receive support, and feel your expertise appreciated is invaluable. Fortunately, I found that the grass is greener in the Newberry School District.

Fallon Griffy is a National Board Certified Teacher (NBCT), a Lower Elementary Montessori educator at Boundary Street Elementary School. This is her 10th year teaching, and nine of those have been in Montessori. She completed her undergraduate degree from the University of South Carolina and obtained her Masters of Instructional Technology from Lander.

Education in Newberry: A Parent-Educator Perspective

Twelve years ago, I made the difficult decision to leave a nearby school district to teach in Newberry County.

It was a personal decision because I was leaving the school I attended as a child in a highly accomplished district. Many schools have been recognized with prestigious awards, such as Palmetto’s Finest, train nationally ranked academic and athletic teams, and offer supplemental programs to all grade levels. In addition, the elementary schools provide magnet programs, foreign languages, pull-out gifted and talented classes, and in-house special services such as physical therapy and occupational therapy.

What made my decision difficult was moving my child from a school that offered these services to one that I naively believed did not.

Now that my son is 21, I often reflect on his time as a student in Newberry County. There was no need for worry.

My son’s teachers at Little Mountain Elementary loved him for the person he is — quiet, smart, and kind. They found ways to challenge his gifts in reading and writing and supported him as he grew to love math. When the stress of middle school became overwhelming at Mid-Carolina Middle, his teachers reassured him, supported his special needs, and continued to challenge him to reach his full potential. And as he advanced through Mid-Carolina High School, he continued to excel academically, receiving credit for many AP courses that transferred as course credit when he started college. He graduated in the top 5% of his class as a Palmetto Fellow, received numerous scholarship offers throughout the state, and has continued his success throughout college. He is now a senior in the Honors College at the University of South Carolina, majoring in accounting.

I recently asked my son what he liked most about attending school in Newberry County. He shared that his favorite grade was seventh grade because his teachers were nice. In high school, he enjoyed being in classes with peers with similar interests and academic goals. He also liked the size of his schools and felt prepared for the future when he graduated.

His opinion of school was not based on test scores, report card ratings, sports records, or special events. It was important to him that he felt safe, valued, and could learn in a clean, respectful environment.

Beginning in kindergarten, teachers in South Carolina are guided by the “Profile of the South Carolina Graduate” principles to prepare our students for life after graduation. Although the School District of Newberry County may not have magnet schools, language immersion programs, and specialized state-of-the-art facilities, students who attend school in Newberry County are well-prepared for college when they graduate. All students receive the special services they need through contracted services if the SDNC does not provide them. Gifted and talented students are served through enrichment by trained educators in each elementary school. Though foreign language is not a part of our elementary school curriculum, our diverse community offers opportunities for students to learn about other cultures.

As part of the education team of Newberry County, I know the teachers within our district are highly trained. We have numerous opportunities yearly to further our education through professional development workshops, conferences, and specialized training. We receive ongoing support through mentors and instructional coaches, access to up-to-date technology, and the instructional resources and materials we need to do our job. Our administrators and district leaders are approachable, resourceful, and supportive as we strive as a team to guide our students toward their full potential. Our district is also fortunate to have a strong relationship with Newberry College as we grow, train, and employ new teachers within our school system.

Parents want only the best for their children. We often use social media, word of mouth, and state report cards to compare teachers, schools, and districts. These resources provide a snapshot into our schools and the future of our communities, and as taxpayers and investors in the community, we want the best education outcomes for our students.

The world of an educator and parent intertwine when a public school teacher has school-aged children.

You must experience things firsthand to truly appreciate the benefits and challenges of varied learning experiences. As a parent who is an educator, I sometimes must release control, responsibility, and outcomes to others. I believe teachers and parents want the very best for their students and children, and both must have faith that others will love and respect their children as much as they do. Considering all these factors as a parent and educator, I would not change my decision to let my son attend school in Newberry County.

Does Newberry offer a well-rounded education that challenges students’ strengths, prepares them for life after graduation, and nurtures them socially and emotionally in our ever-changing world? As a teacher in Newberry County and the parent of a child who attended Newberry schools, I am proud to answer, “Yes, we do!”

Christie Allison is a third-grade teacher at Reuben Elementary School in Newberry, South Carolina. Since graduating from the University of South Carolina (1994), Ms. Allison earned a Master’s in Elementary Education from Catawba College (2000) and became a National Board Certified Teacher (2012). Ms. Allison has worked as a classroom teacher in public schools for over 25 years.

Voces Comunitarias: Honoring Latino Community Voices

As Co-Chair of the 2019 award-winning School Improvement Council (SIC) at Walhalla High School (WHS), we wanted to improve school communication and support for Multilingual Learners (MLL) and their families. Since I was not bilingual and not a member of the Latino community, I knew we had to begin by forming relationships with trusted bilingual community leaders to help us understand our Latino community’s cultural values and needs.

By leveraging the expertise of community leaders, we successfully hosted the first annual School Wellness Community Resource Fair, explicitly designed to welcome and support Latino family members in our school community. Para Todos was held in the old WHS soccer stadium, a space that is walkable and familiar to the Latino community. The event was scheduled to coincide with the yearly WHS Alumni Soccer game. We recruited Latino food vendors and required all community organizations to share materials in Spanish and English. We also had a bilingual staff member available to meet with families. The event was well-attended by Latino families in Walhalla and was so successful it became an annual event.

I still use what I learned through this leadership experience on SIC to guide my work as a Carolina Family Engagement Center Family Liaison.

Modeling many of the family-school-community partnership strategies used in the Para Todos event, the Community Family Resource Center (CRFC) implementation at the Walhalla Branch of the Oconee County Public Library (OCPL) launched in 2022. Under the leadership of Superintendent Molly Spearman, the South Carolina Department of Education (SCDE) partnered with CFEC to develop CRFCs across the state.

These centers are designed to share essential resources to help families support children’s learning and development in places where families typically go shopping, get gas, do laundry, or pay the water bill.

What is unique about the CRFC in Walhalla is that all materials are in English and Spanish. CFEC partnered with Blair Hinson, OCPL Director; Nivia Miranda, Bilingual Facilitator at James M. Brown Elementary School and OCPL board member; and Sarai Melendez, Walhalla City Councilwoman, to ensure that this CRFC was a good fit for our community and a winning solution for all involved.

The staff invests in making the library a community hub and welcoming space for Latino community members. In addition to the CRFC, they employ a part-time social worker, part-time interpreter, and full-time bilingual community member. They intentionally partner with community organizations and bilingual community health workers to host informational events in Spanish and family events that honor the Latino culture. They partner with the local school district to provide free summer meals and serve as a local Food Share program distribution site. All events take place in or adjacent to the CRFC. If families need information about getting the help they need, bilingual staff members and volunteers direct them to the best resources in our community.

All these efforts help build a community of belonging — one relationship at a time.

Recently, new immigrant moms gathered for a workshop at the library where they received free diapers, and their children enjoyed a free meal during the holiday break. These moms had an opportunity to ask volunteer bilingual community health workers questions about accessing healthcare and enrolling their children in school. They expressed surprise that so much help was available at no cost and wondered why community members cared about them; they did not expect to feel accepted in this way. This is another illustration of the power of the Walhalla CRFC.

Many MLL families don’t feel comfortable using resources available at the library or entering their child’s school building to ask for help. Most schools have locked doors and require a picture ID to enter the building. Some schools are ill-equipped to serve families who are English learners, so families may not have access to an interpreter, and materials with important information about their child’s education may not be available in a parent’s home language. Some MLL families face challenges in digital literacy and may only have a grade school education in their home country — making it difficult to know how to navigate the U. S. education system.

CFEC and the Walhalla CRFC help families bridge this gap by providing the resources and support they need to advocate for their child’s learning, development, and educational needs.

CFEC continues to honor the voices of Latino parents in South Carolina. With the help of Councilwoman Melendez, we have recruited Latino parents to serve as a parent advisory group to share their experiences in the educational setting and inform what we do to improve outcomes for MLL students and families. This approach is transformative in that it provides a paradigm shift. Rather than using a top-down or outside-in approach to school and community decision-making, CFEC, in general, and the Walhalla school community, in particular, are learning how to level the playing field by connecting with members of the Latino community. We learn from them directly about what the community needs and how, where, and when to meet their needs.

We cannot effectively advocate for and improve outcomes for MLL students and families without inviting Latino parents and community members to sit at the decision-making table.

This work becomes increasingly important as our Latino student and family population grows across the state. According to data compiled by the Migration Policy Institute, Spanish speakers comprise 70% of South Carolina’s MLL population. The number and diversity of languages spoken by newly arriving immigrant families are also increasing. In addition to Spanish, Russian, Portuguese, Chinese, and Vietnamese are among the top five languages spoken in South Carolina schools. There is a continuing trend of growth of the immigrant population in South Carolina, with a 135.7% increase of foreign-born immigrants and a 28.6% increase in U.S.-born, in South Carolina since 2000, demonstrating the increased diversity within the state’s population. Nearly half of these newly arriving immigrant families have at least one parent in the home who is Limited English Proficient (LEP).

To meet this challenge, schools must find creative solutions to meet language access needs, build culturally responsive relationships, and share decision-making power with MLL families to promote their children’s school success. To learn more about building authentic and intentional family-school-community partnerships, visit the CFEC website and use this toolkit to learn more about setting up a CRFC in your school community.

References

Migration Policy Institute, National Center on Immigrant Integration Policy, “U.S. Young Children (ages 0 to 5) by Dual Language Learner Status: National and State Sociodemographic and Family Profiles” (data tables, MPI, Washington, DC, 2024).

Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), pooled for 2015-19. “State Demographics Data – SC,” accessed February 27, 2024, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/state-profiles/state/demographics/SC

Lorilei Swanson is a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and Licensed Professional Counselor with a PhD in Educational Leadership from Clemson University. She is the Upstate Family Liaison and Project Lead for the Carolina Family Engagement Center (CFEC). CFEC is one of 17 statewide family engagement centers funded by the U.S. Department of Education and housed in the SC School Improvement Council (SC-SIC) at the University of South Carolina College of Education. Its mission is to support family engagement capacity-building for educators and parents and promote equity in opportunity and high academic achievement for all students through effective evidence/research-based family engagement. Before working as a CFEC family liaison, Lorilei was a school-based mental health counselor in the School District of Oconee (SDOC). She also served as Co-Chair of the School Improvement Council (SIC) at Walhalla High School, winning the Dick and Tunky Riley Award for SIC Excellence in 2019.

Parents and Teachers: The Joy of Family Engagement

I was shocked to learn that Ms. G. sent the first LinkedIn connection request for any of my parent/teacher relationships, and I was surprised she took the initiative to communicate with me. Her son, T., was beginning his senior year of high school. I will never forget her as an involved parent with high expectations for her son, and her approach to motherhood taught me the significance of the saying, “It takes a village to raise a child.”

I met Ms. G. three years ago at her son’s 9th grade Individualized Education Program (IEP) meeting. While she was attentive to my proposal for her son’s educational plan for the year, she had her own goals for him and made it clear that she did not like my recommendations. I suggested that T.’s annual goals shift to focusing more on the skills he needed to reach his postsecondary aspiration of becoming a truck driver. Ms. G. simply stated, “This is unacceptable to me. He is in ninth grade and should be reading on a ninth-grade level before we focus on anything else.” My attempts to help shift Ms. G’s focus towards preparing T. for his goal of becoming a truck driver were unsuccessful.

The differing roles between a teacher and a parent were clearer than ever. We both supported T.’s future goal of becoming a truck driver; however, as a supportive teacher with a different perspective, I suggested using T.’s interest in truck driving to improve his reading abilities. Helping T. required me to teach his family the significance of his independence.

Although we are more commonly known for our work with students, teachers help guide families through the transition of releasing parental guidance to independence.

T. was a student in my unique ninth-grade academic support class. There were several students in the class whose mothers had passed away, including sisters who lost their mom two weeks before starting the school year. I connected with the Carolina Family Engagement Center and committed to researching positively influencing parent engagement in student career planning. Despite disagreements, parents like Ms. G. participated in activities that helped make my initiatives successful. My students were motivated to succeed because they had their parents’ support and attention. While I am grateful for the opportunity to impact my student’s success, I’m curious about having a greater impact if allowed to guide students at a younger age. Realizing the opportunity to support young students’ career interests through adolescence is a rewarding journey in teaching and parenting.

Overall, my commitment to the Carolina Family Engagement Center led to more positive communications with parents about their children’s goals, and students were more focused on their academic performance.

My conversations with students and families helped me assess the amount of family time, parental knowledge, and level of independence within each family I served. While some parents accepted my feedback, I realized conversations with parents like Ms. G. were productive for students and families. As a parent, asking my daughter’s teacher questions about her feedback, while uncomfortable, allowed us to have mutual understanding and develop common goals. The same was true for my relationship with Ms. G., and she knew T clearly well, but my communication with her seemed to cause conflict between her and T. at home.

While my class had many discussions with T. about the powerful, positive impact and influence of engaged parents, he did not agree that his mom’s involvement helped him in any way. However, being a mother gave me the opportunity to understand the challenges of parenting and the difficult balance required in teaching independence.

Although I was a fairly new mom, my daughter and I shared many pivotal experiences in her first six years of life. Among other events, her tumultuous birth involved life-threatening moments for both of us, including my having a stroke. As a result, I understood what it felt like to have a disability, have your independence stripped due to a disability, care for someone with a disability, and feel disappointment when you expected to be celebrating.

T.’s family was avoiding the inevitable turning point in parenting: teaching independence. Teaching independence is a very difficult transition when a parent doesn’t allow a child to fail. Therefore, my response to our parent-teacher conflict was guided by my belief that there are many lessons learned directly and indirectly through all life experiences. Ultimately, challenging situations shape people into becoming wiser. Ms. G. needed time to adjust and to accept the reality that T. was growing up, and he wasn’t going to achieve everything she wanted him to on her schedule.

While Ms. G and I never completely agreed, we maintained mutual respect for our unique perspectives, our parent-teacher relationship, and our dedication to T.

By the end of that school year, I reached the conclusion that schools consist of public servants. Public servants, driven by awareness and respect, are a part of the village that every parent hopes to build for their families. Although the year started with my overzealous approach to supporting my daughter through first grade, I soon realized that parents’ influence is limited. Ultimately, teachers hoping to make an impact, like my daughter’s teacher and myself, become a part of the child’s village.

Accepting Ms. G.’s LinkedIn request confirmed she learned the significance of independence and the meaning of “a village.” I thanked her for reaching out to me and wished her and T. well in his senior year of high school. Ms. G. replied, “Yes ma’am. It is a long road, but he is slowly getting back on track. Thank you for everything that you have done. It’s truly appreciated.” Her gratitude was a warm confirmation which taught me that many people contribute to a child’s development and celebrate their success.

Being a part of a village is not limited to teachers, it involves everyone fulfilling their purpose and role. Since we all have a purpose, it is imperative to your village and yourself that you fulfill it.

Dr. Robyn Mixon is a South Carolina native and a Charleston County School District graduate. She resides in Summerville, SC, and currently serves as a Transition Specialist in Dorchester 4 School District. She has worked as a special education educator for the past 20 years, supporting students with various disabilities. Dr. Mixon is strongly committed to impacting students through family engagement.

ELE, IOTA, Opening Retreat

Overview of the ELE Program

Education Leaders Experience (ELE) is a ten-month community-based outreach program for South Carolina education professionals. The ELE program was created by Colonial Life in 2016 and is administered in partnership with the Center for Educational Partnerships (CEP) at the University of South Carolina with facilitation technical assistance by Verbalizing Visions, LLC. The program has over 180 graduates and serves 9 of South Carolina’s counties and over 20 public school systems. In late July, the ELE program welcomed its Iota Cohort participants during an opening retreat, which included two days of leading and learning at the Central Carolina Community Foundation’s Collaboration Zone.

Day 1: Embracing Discomfort and Intrigue

Marie McGehee, Director of Corporate Social Responsibility for Colonial Life, welcomed participants and highlighted the program’s mission to equip leaders with the insights needed to effectively navigate and influence the evolving educational landscape that supports the skills and talents needed in today’s workforce. Cindy Van Buren, Director of the Center for Educational Partnerships, set the stage by emphasizing the College of Education’s unwavering commitment to educators, urging participants to “embrace discomfort” as a catalyst for growth across the retreat.

Share This Story:

Iota Cohort participants gearing up for a productive day.

The day continued with an insightful session led by Ron Harvey, a Certified Leadership Coach and vice President and COO of Global Core Strategies and Consulting. His wisdom and experience captivated the audience. Ron’s philosophy centers around the transformative power of inquiry, encapsulated in his quote, “Questions change the world, not statements.” This idea set the tone for the session, encouraging participants to embrace curiosity and ask the questions that drive meaningful change.

Ron shared a series of impactful insights that resonated deeply with the educators:

- “No matter how good you are, you must be better tomorrow.” This call to continuous improvement inspired participants to strive for excellence every day.

- “If you’re not uncomfortable, chances are you’re not growing.” Ron challenged the group to embrace discomfort as a necessary part of personal and professional growth.

Beyond these powerful statements, Ron emphasized the importance of presence and engagement, urging everyone to “be where your feet are” and fully commit their head and heart to the present moment. He also highlighted the concept of “relationship equity,” comparing it to a credit score where deposits must outnumber withdrawals, building trust and strong connections over time. He also emphasized that participants follow the Platinum Rule in their positions – treating others how they want to be treated, considering their unique backgrounds and preferences. Reflective discussions allowed participants to delve into their personal goals and aspirations, considering how the session’s insights would impact their leadership approach.

Photo: Group discussion during the reflection session.

Ron and his team led the Iota Cohort through multiple interactivities. One participant found his team’s “Sharing the Vision” activity incredibly impactful. The activity required participants to lead their team in recreating a poster that no one in the group could see. This highlighted the leader’s role in developing and sharing a vision while allowing their team to carry the vision. Krysten Douglas reflected,

“This activity drove home several reflective moments for me as a leader. First, we lead through our strengths. And lean into those strengths. Second, other leaders add to our experiences. Lean into recognizing those enhancements. The end product was so much stronger and much more complete because of the efforts and commitments of the group, not just one single leader.”

Participants engaged in the poster activity, working collaboratively without leader intervention.

The day concluded with an evening social hour at Hyatt Place and a hands-on cooking event at Let’s Cook Columbia. These events provided an informal setting for networking and camaraderie, allowing participants to build lasting connections. David McDonald shared, “Being new to the area, I look forward to accessing this network of talent and knowledge to help me grow and learn new ideas and resources available to help grow and learn.”

Attendees at the evening activity, engaging in lively conversation and building connections.

Day 2: Future-Focused Leadership and Learning

The second day began with a warm welcome back and an outline of graduation expectations, setting an enthusiastic tone for the day’s activities.

One of the highlights was the session facilitated by Dr. P. Ann Byrd, Executive Director & Lead Strategist, SC TEACHER. Participants were offered a comprehensive evaluation of leadership styles and effectiveness, providing participants with valuable insights into their leadership capabilities. Susan Hendricks noted, “The leadership assessment helped me examine my areas of strength and areas of opportunity for growth. I will use these results to improve my interactions with my team and get uncomfortable.”

These evaluations didn’t just stop at identifying strengths and weaknesses; they provided actionable insights that participants could take back to their districts. Carolyn Donelan appreciated this opportunity for reflection, stating, “The leadership assessment provided an opportunity for me to reflect on my leadership strengths and concerns. I plan on sharing these results with my staff to discuss ways to follow the Platinum Rule and flex my style to fit their needs.” This session created a platform for leaders to engage in meaningful discussions about their personal growth and how it could translate into their professional environments.

Participants engaged in the poster activity, working collaboratively without leader intervention.

Participants gather to discuss strengths and growth areas based on their leadership style.

Elizabeth Scarbrough, Director of Personalized Professional Learning, CarolinaCrED, and Libby Ortmann, Micro-credential Support Specialist, CarolinaCrED, introduced the concept of personalized professional learning through micro-credentials, emphasizing the importance of continuous growth and adaptation. This session underscored the need for leaders to remain flexible and open to new learning opportunities. Participants in the cohort are encouraged to complete a micro-credential throughout the program. Sid Parrish, one of the Iota Cohort members, already knows his micro-credential and shared, “After reflecting on the presentations by Ron Harvey and team, and the leadership style assessment, I will complete the micro-credential in managing change.”

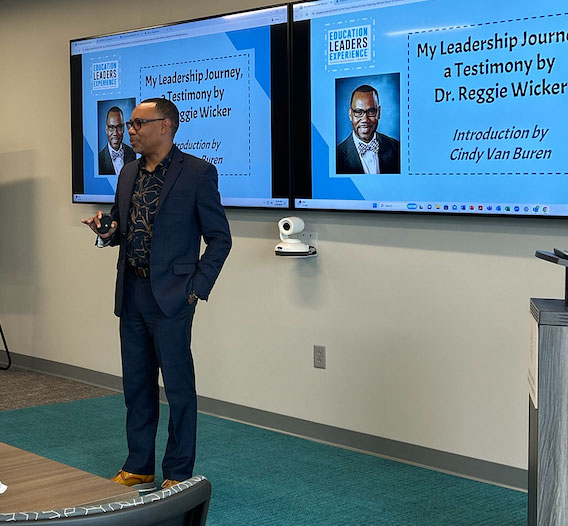

A compelling testimony by Dr. Reggie Wicker, Director of Human Resources for School District Five of Lexington and Richland Counties, titled “My Leadership Journey,” inspired attendees with real-world experiences and insights, reinforcing the importance of perseverance and vision in leadership. Dr. Wicker shared, “When you come into spaces and places, you never know what someone’s going through.” He emphasized that the people who supported him in his journey while showing empathy never allowed him to lower his expectations. This balanced approach of support and high standards was pivotal in his development. Dr. Wicker also reminded everyone, “Don’t take for granted the role that you play in a child’s life,” underscoring educators’ profound impact on their students. Inspired by Dr. Wickers’s testimony, Deanna Taylor shared that she determined her list of influencers and planned to send a token of appreciation to each person.

Participants explore micro-credentials to determine which to complete.

Dr. Reggie Wicker shares his leadership journey.

The ELE Opening Retreat provided a foundational experience for the Iota Cohort, fostering collaboration, growth, and reflection. The diverse insights and experiences shared over the two days set the stage for a year of impactful leadership development and community building. Felicia Madden encapsulated the spirit of the retreat, saying, “ELE allowed me the time and space to be around a diverse group of educators to gain knowledge and ideas to take back to my district. I am excited to make new relationships and connections to move my district forward.”

Special thanks to Dupre Catering and Publico-Bull Street for ensuring our participants were well cared for and Hyatt Place in the Vista for hosting us for two days.

Knock, Knock: Who’s There? Paid Student Teaching

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

This story’s narrator is a composite character based on student teachers who shared their experiences regarding paid internships through qualitative survey data.

Teaching teddy bears, producing homemade playdough, creating characters’ costumes, and recycling instructional resources. This was my childhood as the daughter of a kindergarten teacher. Early on, I experienced the passion, purpose, and power of the education profession. I was determined to follow in the footsteps of my educator ancestors.

Flash forward to my 21st year of life and senior year of university studies. I was continuing to progress in my teacher education program when opportunity knocked and unexpected information simultaneously knocked me down.

Across the nation, negative news bemoaning the severity of our nation’s teacher shortage flashed across the headlines of multiple media sources. Diverse solutions had been proposed, but the education profession was repeating old patterns by doing the same thing over and over again expecting a different outcome. Hope-filled future teachers continued down the path of traditional student-teaching scenarios while the teacher shortages deepened.

And then something different happened.

During the summer of 2015, the state of South Carolina announced an innovative opportunity for well-prepared student teachers. State department-initiated internship certificates came into being, and I leapt at the chance to become a teacher of my very own classroom while concurrently finishing the final semester of my educator preparation program. The caveats were significant, but I was ready, willing, and able with a high GPA, my professors’ approbation, passing scores on my content area teacher certification exams, and an ambition to excel. The icing on the cake was the news that this would be a paid internship.

Was I prepared for this massive responsibility? Would there be enough support in place? Would my students succeed?

Brimming with questions, I remained enthusiastic about the possibility of contributing to the teacher shortage solution in my own backyard and earning compensation as I honed my craft of becoming an exemplary educator.

In the blink of an eye, I went from college student to full-time teacher.

Will this paid practice persist? My fervent hope is that my struggles and my successes will facilitate positive change and help to enhance our profession. I think about my tale of salaried, solo teaching before graduation with the acronym of BATS: Balance, Acceptance, Team, and Self-Selected Supports.

Balance

The importance of work-life balance was addressed in my freshman seminar course and interlaced throughout some of my educator preparation pedagogy courses. It took my first week of student- teaching to recognize the realities of what balance really meant. My new bedtime became eight o’clock! I had never been so exhausted in my entire life. It was easy to take work home and to obsess over my teacher obligations or to take ownership of student, parent, and colleague challenges. Gaining life balance through this experience added to my resilience and kept me in a positive state of mindfulness and gratitude. Over time and with support, I became energized rather than depleted.

Acceptance

In my capstone philosophy of education paper, I emphasized the acceptance and inclusion of all students. But I soon realized that the power of acceptance is not just about students. I too was seeking acceptance in a new school community filled with experienced educators. I felt like a lone fish in a deep sea, but the slow process of gaining teacher friends, forming harmonious relationships, and letting go of things that really did not matter provided the path I needed to accomplish goals and gain acceptance.

Teams

Being part of a collaborative team is a necessity for novice teachers. My kindergarten team consisted of an eclectic mix of professionals with 3 to 30 years of diverse teaching experiences. Learning is a social process, so growing in my profession with the help of my team was no different from the learning experiences of my students. Planning, prioritizing, praying, and even partying and celebrating together made my internship experience both palatable and pleasurable.

Self-Selected Support

Another component of the internship certificate process is assigned mentorship. Each intern is assigned a mentor. Often, assigned mentors are teachers within the same grade level, so the planning period is concurrent with their mentee’s. Sometimes shared time may not be feasible which can lead to challenges.

My saving grace was a self-selected support system.

I found a mentor extraordinaire who was kind, caring, and a kindred spirit. Mentorship is key to a novice teacher’s survival, and finding one who fits through self-selection can be more valuable than formally assigned mentors.

The bottom line is that my internship certification semester was a bumpy road that started me on the path to my profession in which I am continuing to love, grow, share, and shine. For that initial experience, I will be forever grateful.

My unexpected knock arrived the fourth week of my internship life.

I received news pertaining to my hero, my first teacher, my confidant, my best friend, and a kindergarten teacher of 24 years: my mom. She was diagnosed with stage five breast cancer. My world was shattered, and within six short weeks, my anchor was gone.

I share this because being a teacher is tough, and if I, as a novice internship teacher, can survive and thrive during a time of trauma and grief, then others can too. My mom taught me to love, appreciate, and “keep on, keeping on.” She wanted to make the world a better place one student at a time.

Everything has come full circle because I am now walking in my mom’s footsteps as a kindergarten teacher who was kindled by the opportunity of a paid internship. This opportunity

occurred during a dark time but brought light to my life and the education profession.

This opportunity occurred during a dark time but brought light to my life and the education profession.

Paid internships are not the only solution to offset our shrinking population of teachers, but it is one of the viable possibilities. It worked for me, and I encourage others to embrace this

opportunity. Seasoned teachers and administrators must continue to accept new means of growing teachers and step up as official and unofficial mentors for their newest colleagues: paid interns. Helping to create a team and form new collegial relationships are essential ingredients for the success of both novice and veteran teachers.

The face of education is changing. Being open to new and creative means of teacher preparation is a step toward having continual, competent, and caring teachers in all South Carolina classrooms.

Share This Story:

Susan Fernandez

Dr. Susan Fernandez is the Dean of Teacher Education at Newberry College in Newberry, S.C. She has over 40 years of experience in the education profession in a diversity of roles as a classroom teacher, literacy coach, professor, and administrator. Dr. Fernandez earned her undergraduate elementary education degree and master’s degree in literacy from Clemson University and her Doctor of Education in educational leadership and social justice from Union Institute & University.

This story is published as part of a recent storytelling retreat hosted by CarolinaCrED, housed in the University of South Carolina’s College of Education. Mira Education, a CarolinaCrED partner, facilitated the retreat and provided editorial and publication support. Learn more about this work and read additional stories by following @CarolinaCrED and @miraeducation.

Cultivating a Culture of Collaboration: Pivoting at a Professional Development School

ABSTRACT

This article, written by a third-grade teacher, provides a first-hand account of collaboration and reflection with a student teacher intern while teaching in a Professional Development School (school-university partnership school) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The teacher details the process of pivoting during technology issues before and during instruction.

NAPDS NINE ESSENTIALS (2nd Edition) ADDRESSED IN THIS ARTICLE:

- A professional development school (PDS) is a learning community guided by a comprehensive, articulated mission that is broader than the goals of any single partner, and that aims to advance equity, antiracism, and social justice within and among schools, colleges/universities, and their respective community and professional partners.

- A PDS embraces the preparation of educators through clinical practice.

- A PDS is a context for continuous professional learning and leading for all participants, guided by need and a spirit and practice of inquiry.

- A PDS makes a shared commitment to reflective practice, responsive innovation, and generative knowledge.

- A PDS is a community that engages in collaborative research and participates in the public sharing of results in a variety of outlets.

A lone ballerina with her toe down, head up, constantly spinning is the image I conjure when I think of pivoting. Yet my experiences with pivoting are vastly different and less graceful. During a global pandemic, these experiences have multiplied.

At 5:30 p.m. my district’s Google Suite disappeared.

At 5:30 a.m. the next morning, the Google Suite is still down.

Walking to the classroom takes forever; the hallway extends another 30 feet. I mumble, wave, and smile at my colleagues hiding a heavy cloak of anxiety. I begin to think about the implications of not having access to Google Suite and its impact on my students. My concern is escalating.

I teach third-grade students. Most years, I have about 17 students on my roster. This year is different. I still teach third grade, but now I have 28 students. The drastic change in class size is due to teaching through a global pandemic. In the age of COVID-19, changes to how we think about teaching and learning are a part of our “new normal” as educators. Not only has the number of students on my roster increased, but I am also teaching in a unique setting. I am a virtual teacher, and I teach all of my students online. All of my lesson materials are online, and students access them through Google Suite.

I take a deep breath and start the mental process of pivoting.

Up until this point, I knew that teaching through a pandemic had its challenges, but to date, this is the moment that is most out of my sphere of control. In my peripheral view, a figure emerges in the classroom doorway. It’s my intern. In the light of her smile, I am able to mask some of my anxious thoughts because as they say, “The show must go on.”

I don’t inform her of the power outage because I feel sure somebody from the district office will cancel school. I turn my cell phone on a very loud chime so as not to miss an email stating such.

No one from the district cancels school, so my principal does not send the text. Bridget and I exchange pleasantries.

Over the course of 14 weeks, Bridget has become acquainted with the students. She led small groups during synchronous times, using her own Google classroom as a breakout room. In the beginning of her leading small groups, she was a little unsettled because students were not as responsive as she remembered in her previous face-to-face placement. I confided in her that I felt the same pang of rejection. I reassured her that giving students her focused attention in small groups is impactful in a virtual setting and that with time they would respond. I modeled elaborating on one student’s response and having students respond to each other by providing prompts such as “I agree with Kamarie,” and, “I would like to add….” As the semester continued, Bridget’s pivot was illustrated through her ability to facilitate discussion through peer-to-peer communication, which led to increased observable student engagement.

I gently break the news to her about the Google Suite outage. In her eyes, I anticipate my students’ worry. I know that when students become aware of the outage, they will fret over what to do in the interim. Her eyes suggest she is waiting for an alternative plan, just like my students will.

I hope I reflect an air of confidence.

It is now 7:31 a.m. and still no Google Suite, but we do have the internet.

As a mentor teacher, I am aware that presentation matters as mentees are impressionable. So, I remain calm even though I am in knots on the inside. I take a mental retreat to a situation when professionalism was practiced in the face of pivoting.

Prior support came in the form of collaborative moments with our university partnerliaison, Dr. Thompson. Killian Elementary is a professional development school (PDS), which means that we have an ongoing and reciprocal partnership with the University of South Carolina. Our liaison of 20 years has dual roles at Killian: when he is not teaching an immersion science methods course to preservice teachers, he is supporting faculty with professional development. For three years, we have practiced professionalism as we have co-planned and collaborated on teaching full science units that incorporate what he calls “sense-making” activities. We share in making and collecting knowledge from our shared experiences; our work enables both tall teachers (the adult teaching candidates) and small teachers (the children) to have lots of opportunities to make sense of difficult science concepts like erosion and weathering.

For instance, we spend time after every lesson reflecting and pivoting for the next session. During one reflection session, we noticed that there was not enough time to teach the full cycle of a guided inquiry science lesson in one class period, so we decided to chunk the components across a three-week lesson sequence. This pivot made a positive impact on student engagement as we noticed that his students, the tall teachers, were able to concentrate on one part of the inquiry at a time, and my students, the small teachers, were better able to articulate science thinking within small groups. And I, through this professional pivoting paradigm, have moved from needing scaffolds to teach to planning units of study on my own. Ultimately, we noticed where we needed to adjust our plans to meet the needs of learners. Our relationship strengthens our shared collegial pursuits; I was interested in becoming a better science teacher and he was interested in giving preservice teachers authentic experiences in a classroom. Those times of collaboration prepared me for this moment when I need to illustrate to my intern what to do when what you plan has to shift due to circumstances outside of our control.

We sit for a moment and gather our thoughts.

The applications and extensions in Google Suite are easy to use and student-friendly. I hyperlink websites into the lesson plan. Websites such as Readworks.org, Flocabulary, and, my favorite, Nearpod are class staples. I have spent the first nine weeks creating videos using WeVideo for core content and explaining how to access and enter various websites. During check-in times, my students started sharing shortcuts they use to navigate the internet, and I captured their demonstrations in multiple videos. At that moment I realize that my students are prepared to pivot alongside us.

On opposite sides of the room, we begin to plan an asynchronous lesson for the students called a student pathway. We collaborate on a shared document before we create a lesson plan for students. Teaching through a pandemic is innovative. We begin to brainstorm a lesson. Today is Veterans Day. So, we set out to design a student pathway about “Thanking A Veteran” using the Wakelet multimedia tool. As a colleague, she offers her expertise, and together we craft a learning module for our students. Because of the need to shift today’s plan, Bridget is able to experience not only the demands of our profession but also the rewards. Our mission is complete.

It’s 8:15 a.m. The Google Suite is still down, but together we pivot toward possibility.

How will you use your support system to become an agent of change in your school context? What will you do to ensure that preservice teachers get the practical experience of collaborating even during a pandemic? What expertise will you model to ensure preservice teachers have authentic and meaningful experiences before they have a class of their own?

Teaching through a pandemic has been challenging, yet my image of pivoting has expanded beyond graceful ballerinas. My experiences with pivoting are grounded in the daily cultivation of practicing professionalism as an educator. Being reflective, supportive, and collaborative is my new image of pivoting.

Aisja Jones (ajaisjajones@gmail.com) is a third-grade teacher at Killian STEAM Magnet Elementary, doctoral student at University of South Carolina, mentor teacher, and PDS Fellow

Share This Story:

Aisja Jones

Aisja Jones is a third-grade teacher at Killian STEAM Magnet Elementary, doctoral student at University of South Carolina, mentor teacher, and PDS Fellow.

Attending to Challenges, Supplying a Teacher Workforce: How South Carolina Can Support Alternative Certification Pathways

That teacher over there. Yes, that’s the one.

The one demonstrating strong relationships with her students. The one with 12 years in the profession. She understands the skills needed for the workforce.

She’s also the one whose mother is in the hospital. The one who showed up every day during the pandemic.

Her? Yes, her. She’s not certified. She’s facing a barrier. She needs to pass Praxis, a national educator assessment for certification.

Alternative certification works, but how do we attend to challenges to the alternative certification process?

I am an alternatively certified teacher.

I know and understand the challenges to certification in South Carolina for people who would like to enter the profession and actualize their dream of becoming a teacher. These include limited access to entrance into educational programs, insufficient funds to complete a degree program, student teaching full time without a source of income, a low college GPA, and passing Praxis. Passing Praxis stands as a hurdle for many. Specifically, licensing exams have a disproportionate impact on minority teacher candidates: 62% of Black and 43% of Hispanic candidates fail the elementary Praxis test even after multiple attempts.

Some time ago, states tightened up requirements for teacher licensing. Instead of removing challenges, they contend that tighter regulation of teacher training programs and additional requirements on the pathway to certification are the only solutions. Although well-meaning, such submissions are not based on sound research or factual data

Now, faced with a national teacher shortage as states report their supply and demand data, the impact those efforts are having on teacher diversity, coupled with evidence that Black and Latinx students benefit from having teachers who look like them, some states are moving to loosen or even dispense with some requirements. For example, Arkansas rallied to raise its teacher certification test cut score, but considering the shortage, has left the cut score as is.

Too often energy, time, and money are put into “hoop jumping” by candidates with nothing to show for their efforts. South Carolina policymakers have a responsibility and duty to increase, diversify, and qualify South Carolina’s educator workforce for our children. The shortage is even more acute than currently estimated. Qualifications for certification should align with proof of meaningful research-based practices for improving the educational welfare of all students, considering state requirements and state assessment proficiency scores are not the same.

Teachers are planners.

Teachers are proactive.

Teachers are problem solvers.

Teachers are professionals.

But teachers’ spirits, their tenacity, their drive, their ability to overcome all things can be stifled, muffled, dimmed, altered, and diminished by consistent challenges.

As with traditional certification, we must streamline the process to alternative certification so that even more future educators can begin making a difference for students, parents, the community, and the profession.

Today’s college graduates have numerous career options and opportunities. If the path into teaching is too burdensome or costly, graduates will abandon it for other professional pathways (Finn, 2001). As with traditional certification, we must streamline the process to alternative certification so that even more future educators can begin making a difference for students, parents, the community, and the profession.

New Jersey, Massachusetts, Florida, Washington, and Colorado rank as the top states for education. These states provide professional preparation and education for would-be teachers by allowing them to work and learn simultaneously, putting into daily application what they are learning in theory (Department of Education, n.d.). For example, in the state of New Jersey, in order to obtain a standard certificate, all novice teachers must complete the Provisional Teacher Process (PTP), during which they are evaluated, mentored, and supervised by their district or school while working under a provisional certificate. A candidate must obtain a Certificate of Eligibility with Advanced Standing (CEAS) or Certificate of Eligibility (CE). These certificates allow the candidate to seek and accept offers of employment as teachers while completing coursework toward a standard license. The support of mentors, apprenticeships, and instructional coaching helps alternative certification-seeking candidates to be successful, ensuring program quality and constructs which align with student outcomes.

The single approach of teaching while earning certification helps to mitigate economic barriers for many.

South Carolina also has strong examples of alternative certification pathways that work. Carolina Collaborative for Alternative Preparation, also known as CarolinaCAP, is a collaborative effort among South Carolina school districts, the University of South Carolina, and the Mira Education. CarolinaCAP provides the opportunity for paraprofessionals and industryknowledgeable candidates to become certified through graduate-level coursework, microcredentials, coaching, and collaborative inquiry. Applicants must possess a bachelor’s degree from a regionally accredited college and have a minimum 2.5 cumulative grade point average. Applicants applying for certification in Early Childhood Education, Elementary Education, and Special Education: Multi-Categorical (PK–Grade 12) need a minimum 2.75 undergraduate grade point average. Having these qualifying requirements and after passing Praxis, applicants move to candidates and may become the Teacher of Record, taking the lead in their own classrooms through Eligibility of Employment.

The single approach of teaching while earning certification helps to mitigate economic barriers for many.

CarolinaCAP attracts diverse candidates who mirror the student populations they serve. Representation is critical for students (our state’s future teacher pipeline). Eighty-one percent of candidates who participated in CarolinaCAP identify as Black, ranging in age from 20 to 60 years old. Eighteen percent of candidates are male (CarolinaCrED, 2021). CarolinaCAP candidates bring a wealth of both life and professional experiences to their classrooms.The program’s structure addresses the economic barrier as well. Along with the aforementioned requirements, candidates who pass Praxis and become eligible for employment may begin receiving a teachers salary.

How does this translate to the person? The educators trained under alternatively certified programs such as CarolinaCAP might provide some insight. Anisha is a second-year teacher working in a rural district. She’s producing students who will leave second-grade reading and writing with confidence. She’s also a teacher who is having challenges passing the Praxis certification exam.

This is Anisha’s challenge.

She has attempted the exam. She has noticed the longer she teaches, the more she feels Praxis is assessing her instructional classroom practices. Her score has increased each time. But her initial journey was very stressful. She knows a test “doesn’t make you who you are,” but for a person like Anisha, whose heart is in teaching, it “messes with your mind. It makes you say, ‘Gosh, I went to school, and I can’t even pass a certification test.’” Anisha has taught for two years, serving in the roles of interventionist and teacher. She has strong relationships with her students and works with all of them, regardless of how many she has, to ensure they are performing at or above grade level in reading comprehension and math.

I see myself in Anisha, once a new teacher facing a hurdle to becoming fully certified. How do I support her by removing obstacles which do not align with student outcomes?

Anisha has also taken the Praxis test five times. She notes, “When I saw my score go up, it made me feel a little better. But having to keep dishing out that money, I know something has to go lacking because of the test. But I have to do it because my job requires me to be certified.” Anisha is a single mom and among many who have to tackle the financial hurdle associated with repeated testing.

The path to certification will give Anisha the opportunity to be able to live out a dream and weave a connection with students and families for years to come. Certification will give her the final piece of being confident in herself and in growing the educational development of students.

I see myself in Anisha, once a new teacher facing a hurdle to becoming fully certified. How do I support her by removing obstacles which do not align with student outcomes? Obstacles that initially decreased the number of teachers in the profession? Obstacles that marginalize people who have limited economic, social, or educational resources?

A South Carolina Solution

South Carolina has made strides in opening the door to alternative certification.

But it’s not enough.

Statewide programs like Program of Alternative Certification for Educators (PACE) and Centers for the Re-Education and Advancement of Teachers in Special Education and Related Services Personnel (SC CREATE) allow candidates from anywhere in the state to seek certification. Locally based programs, such as Alternative Pathways to Educator Certification (APEC), Carolina Collaborative for Alternative Preparation (CarolinaCAP), and Educator Preparation and Innovation Pathways (EPI), focus their efforts in certain geographical areas of the state. Additionally, some programs such as Teach for America (TFA) seek to bring top candidates to rural areas in South Carolina.

Despite these efforts, there are still challenges to certification.

Some programs only serve secondary candidates, those looking to pursue special education, those who live in the Midlands, or those residing in rural counties.

South Carolina has made strides in opening the door to alternative certification.

South Carolina can do even better. What if we add to these options and create a solution that works in every district, hometown, and classroom, whether candidates are in the upstate region seeking to become certified in elementary or residing in rural Jasper County seeking to teach chemistry? What if this model pulled together resources versus requiring school districts to compete for them? What if this model could be adapted to fit the needs of individual districts without feeling “cookie-cutter” while promoting quality, research, rigor, and best practices? What if this model incorporated local ownership or even allowed smaller districts to collaborate to ensure candidates were exposed to full-scale opportunities? What if we grew our own?

The Tennessee Department of Education has developed a Grow Your Own teacher pipeline program as a partnership between the Clarksville-Montgomery school system and the Austin Peay State University’s Teacher Residency program. The program paves the way for teaching and educator workforce development nationwide. The state-approved Teacher Occupation Apprenticeship programs between school districts and educator preparation programs (EPPs) are now among many Grow Your Own programs in the state of Tennessee offering free opportunities to become a teacher, thus clearing the path for any other state or territory to launch similar programs with federal approval.

The program allows participants to earn a wage while learning to become teachers. Applicants have the opportunity to participate in an alternative route to certification by working directly under the guidance of a skilled, certified teacher. The partnership model includes both two- and four-year colleges and has developed three different pathways for educational assistants to earn their degrees or certifications in teaching.

The model provides other states the opportunity to structure programming to their specific needs. States can target high school seniors, paraprofessionals, or those who already have degrees and need a pathway to strengthen their knowledge in pedagogy and research-based practices.

Policymakers, will you advocate for this solution? Concerned citizens, will you support the policymakers who pledge to adopt this? Parents, will you hold our Department of Education and its stakeholders responsible for making this a reality? School board members, will you advocate for a statewide approach requiring federal approval and involve the state’s educational entities? It must be an approach that can serve every school in every district and every student in every classroom and aligns local resources with community support and community ownership.

Will you ensure South Carolina has numerous educators with diversified backgrounds who represent the landscape of our future workforce?

You!

Yes, YOU, racing your eyes across the page, coming to grips with your responsibility as a reader of this story, will you ensure South Carolina has numerous educators with diversified backgrounds who represent the landscape of our future workforce? South Carolina has made progress, but there is more to be done.

South Carolina is ready. Are you?

Support inclusive pathways which will capture the exquisite talent of our state. Encourage your senator to further explore Tennessee’s national model for a teacher residency program. This same Grow Your Own approach can be successful in South Carolina.

According to the February 2022 Supply and Demand Update report, there were a total of 7,870 teacher departures (resignations) and a total of 2,154 teacher vacancies/positions in South Carolina schools up to February 2022 during the 2021–2022 school year. If I do nothing else, if we do nothing else, we are certain those numbers will increase. If you and I take up this call to action, we will begin investigating additional alternative pathways that support building South Carolina’s workforce, increasing future teachers’ capacities, and filling South Carolina’s classrooms. We further awaken the senses and the abilities of others to demand a solution for our children, families, homes, communities, and our state.

And we successfully dismantle obstacles and challenges—for you, for me, and for the numerous Anishas in the State of South Carolina.

References

CarolinaCrED. (2021). CarolinaCAP Year Two Annual Report. https://carolinacred.org/carolinacap-year-two-annual-report/

Department of Education. (n.d.). Recruitment, Preparation and Induction. https://www.nj.gov/education/rpi/induction/

Finn, C. (2001). Removing the barriers for teacher candidates. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/removing-the-barriers-for-teacher-candidates

Share This Story:

Share This Story:

Remona Jenkins

Dr. Remona Jenkins is the Director of Teacher Quality and Staff Development for the Kershaw County School District. In that role, she guides staff development, alternative certification, the onboarding process for first year teachers, and recruitment efforts in the Kershaw County School District (KCSD). Prior to her work in KCSD, Jenkins served as a district administrator overseeing new hire orientation, teacher induction, international teachers, and the National Board program. She also provided intensive instructional coaching to traditionally and alternatively certified K-12 educators. Her educational background includes a doctorate in education and a master’s in educational leadership from American College of Education, a master’s in elementary education from the University of Phoenix, and a master’s in community and occupational programs in education from the University of South Carolina. Jenkins completed her bachelor’s degree in human development and family studies from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She is married with two children.

This story is published as part of a recent storytelling retreat hosted by CarolinaCrED, housed in the University of South Carolina’s College of Education. Mira Education, a CarolinaCrED partner, facilitated the retreat and provided editorial and publication support. Learn more about this work and read additional stories by following @CarolinaCrED and @miraeducation.

It Takes a Village, and That’s Ok

Have you ever been so tired you can’t see straight? So tired you can’t even sleep? There’s not enough melatonin or essential oil diffusing that can cure the tired I’m talking about. I mean, the kind of tired where the inside of your body hurts.

That’s where I was.

Every situation that came across my desk, phone, or computer was a FIRE. Nine times out of ten, they weren’t even perceived fires, they were real emergencies that involved the health of a student, legal implications, irate parents, worn out teachers — you know the situations.

Ya’ll, I was exhausted. I was tired of being a leader. I had no motivation. I was about one revision away from submitting my resume to Target (love Target, no slight to them, just the place I think about when I consider a career change).

Being a leader takes a lot out of you, and I finally came to the realization that I had to admit defeat. But wait — leaders don’t do that! They don’t let their people see that they’re struggling! What a conundrum I was facing: admit that I can’t meet expectations anymore (hindsight will tell me they were my own expectations, not the expectations of others) or keep dragging my body through the grind every day?

When I stopped to consider this question, I found myself going way back to before I was a leader. What I found was that I don’t ever remember NOT leading. Ever. When I think back to elementary school, I was always trying to “lead” others, even if it meant not considering what I needed. Isn’t that crazy? At the ripe old age of nine, I remember being in Mrs. Hunter’s class trying to rally my classmates to get an extra recess just because my best friend, Jennifer, wanted to climb on the monkey bars again (which, by the way, I was successful in this negotiation — twice).

Upon reflection of my leadership journey, I realized that even though I always thought I hated cliches, it turns out I live my leadership life by them implicitly. Go figure!