Una confianza perdida, otra regenerada

The work of the Carolina Family Engagement Center (CFEC) is focused primarily on underserved families and their students (low income, English learners, those with disabilities, those in foster care, migrants, homeless, and marginalized communities). Housed within the SC School Improvement Council (SC-SIC) at the University of South Carolina College of Education, CFEC provides tools, trainings, and materials statewide through its website and other venues.

By: Julia Beaty, MSW, LISW-CP

I knew this route by heart: one long stretch through the city, a turn onto a county road, and another turn onto the unpaved road, left muddied today, before I turned right — into the place where hopes and dreams hung cautiously in the air. With my fair-skinned face a visible mismatch in the community, for once I was grateful for my unmistakable, obnoxiously colored vehicle that no covert operation would use coming into this community.

Arriving as the sun’s rays dimmed the wet, red clay leading to her home, I made my way to the familiar, weathered wooden steps, carefully minding the toys precariously placed, evidence of an afternoon of delight for her two young children. Two raps on the front door, then three, my usual greeting, followed by “Hola, muy buenas tardes,” through my native accent, native to South Carolina that is.

She welcomed me in, wearing a smile wearied by what I had come to recognize as the loving, faithful concern of a mother whose parenthood was a heavier journey than most. A pink, squealing swirl of a child peeked out from the corner, crumbs of galleta falling from her plump cheeks as she locked eyes with the funny gringa at the door, a mischievous smile of welcome quickly appearing on her face. Across the room sat the mother’s eldest child, absorbed in the world of his sacred afternoon routine: a toy car and afterschool snack of galletas con leche on the kitchen table.

We exchanged pleasantries as her day’s anxieties quickly surfaced, with a question of when the new therapists would be able to come help, paperwork still tied up with a state-level office where I’d submitted it for review, part of my role as his case manager. His behavior, his communication, his stubbornness, and that teacher—all sources of distress for this mother— explained through an almost convincingly flat affect… but I recognized the imperceptible tightness in her face, holding back what might be an eternity of tears, waiting to be released.

Tears for her homeland, her extended family, her dreams of a physically present spouse, her vision of motherhood with typically-abled children, her ability to live without fear of questions about “papers” hiding behind every corner.

She poured herself out each day, rising early to soothe the soul of her anxious-hearted son, giving him all that she could before he was transported to school to begin another day of surviving learning. Her warm, loving embrace snuggled him close before she planted a kiss on his forehead above fear-filled eyes, his reluctance visible, despite the barely risen sun of late-autumn, rays filtering through tall pines. He trudged heavily up the steps: one, two, three, four, five, taking his seat with other students on the petite, orange bus, while prayers in her native Spanish covered him in blessings, petitions, and pleadings for merciful understanding from the teacher that would receive this mother’s precious son for another day.

Two waves quickly crashed down in the room, one of relieved partnership on her and one of uncertain anticipation on me.

“¡Por favor!” she animatedly answered when I offered to attend the upcoming IEP meeting at her son’s school, after translating the letter that had been sent home—in English—with notice so short that her palpable anxiety started to make its way into my mind, too.

Knowing her desired expectations for her son and his learning experience, as well as a less than noteworthy history with his teacher over the prior school year, I realized I’d stopped breathing… I was bracing myself for battle: clarity, communication, power, resources, and trust on the line. One deep breath in, one out, wiggling my toes to re-ground myself amidst the swirl of thoughts, mental notes, and trepidation so I could offer her one gift of hope before leaving.

“Sí, yo asistiré consigo,” I said quickly, before losing the nerve to commit.

Two waves quickly crashed down in the room, one of relieved partnership on her and one of uncertain anticipation on me.

***

It was a chilly morning, a slow-motion walk from my vehicle, filled with butterflies and mental rehearsal, scanning the horizon for her as I made my way to the front door. I pushed the button, stated my name, my purpose, showed my state-issued ID, and was then permitted entrance into the building. Would she be so fortunate with the unlabeled, impersonal metal button or the thick southern drawl communicating the same instructions I’d just heard?

As I passed through the door, I glanced over my shoulder to see her coming, the exhaust from a neighbor’s vehicle contrasted against the cold air of the morning as it drove away. Her red scarf and black winter coat jostled as her dark blue jeans and black tennis shoes ran toward the building, front door open for her, with my simple gift of a trusted, welcoming smile extended; she exhaled a relieved “Gracias” as she passed through the entryway and we walked, together, to get our visitor’s passes from the thicker-than-honey, southern-drawled secretary. “IEP Meeting” I stated, and we were given our passes and directions—in English—to the conference room where the administrator, staff, and professional team members were esperándonos, though we had both arrived ahead of the start time stated in the letter.

Inconvenience, nerves, exhaustion, power, and indifference were all seated around the table when we walked through the conference room door.

With their stacks of papers in hand and conversation already in progress, we sheepishly entered the conference room, looking to see how we could fit a second chair next to the only empty one at the table. Six voices spoke over one another as she and I hurriedly made space at the table and took our seats. Introductions began quickly, and a wave of relief washed over me as he introduced himself: el intérprete! “At least that makes three of us,” I thought as we started the meeting, grateful for another ally at the table who would offer support.

Inconvenience, nerves, exhaustion, power, and indifference were all seated around the table when we walked through the conference room door.

Overfilled schedules and intentions of leaving part-way through the meeting were announced by multiple team members; their expertise and knowledge of her son would be limited to the two-to -threeminute summaries of progress they could offer that morning. Frustrated by this meeting before it had really even begun, I started taking notes: names, roles, observations, and recommendations, writing furiously as the information poured out from the experts, their legs visibly readied to exit stage left the instant that their part in the drama had concluded. Intermittent flurries of Spanish traveled across the table with such sparse detail I was glad I’d been taking notes, wondering when el intérprete would share the summary of what had already transpired.

One, two, three left the room, and suddenly, the teacher, vice principal, and interpreter’s chairs were the only ones still filled apart from ours. I glanced over at her, noticing that the color in her caramel-colored cheeks had changed to a warmer, reddish hue and her eyes were filling with tears as the teacher’s explanation of her son’s limited participation and motivation in the classroom this semester was interpreted casually into Spanish, with a cool indifference in el intérprete’s voice. Before I knew it, tears and her voice, angered by misrepresentation of her son whose desires and capacities she knew better than anyone at the table, rose above the tenuous narrative that was being relayed. Love for her child, an insistence on justice, and a powerful, maternal confidence of her child’s needs and abilities filled the notably vacuous room as her impassioned voice spoke with authority in her native tongue, citing poor communication, failures on the teacher’s part the school year prior, and the empty promises that the teacher had offered to support her son over the summer.

A paltry, anemic summary was offered by el intérprete, leaving me with doubt about what meeting he was attending.

I could feel my heart rate rising, an outcry of injustice and pressure to set the record straight welling up inside me and coursing through my veins, countered by an equally strong current of fear: being accused of misrepresentation, non-native linguistic status, and interjecting as an undesignated communication broker. “Am I breathing?” I wondered as time slowed around me, simultaneously taking in the detail of her worried expression, the casual posture of el intérprete, the now-worried expression of the teacher, and the suspiciouslyraised eyebrow of the first-year vice principal, knowing all that was at stake for her son’s education, and the chasm between what had been communicated and what had been interpreted.

“That’s not all she said!” I exclaimed loudly, powerfully looking across the table at el intérprete, quickly turning my head toward the vice principal with unambiguous passion and conviction.

With those five words, emotional shrapnel went flying through the conference room as blood drained from el intérprete’s face, a mother’s deepest fears were validated, a teacher’s empty promises were exposed, and an administrator’s suspicions of incomplete details of a student’s barriers to learning were confirmed.

“I thought I wasn’t getting the whole story; what exactly did she say?” asked the vice principal. Locking eyes with el intérprete across the table, I dared him to not interpret every word and sentiment of this mother. Not overstepping my role, we exchanged a knowing glance that I was oyendo a cada palabra, so he’d better be precise, and he’d better be thorough. For what was likely the first time, she was able to share her experience, knowledge, and expertise of her son and his needs in school, and she was heard.

For what was likely the first time, she was able to share her experience, knowledge, and expertise of her son and his needs in school, and she was heard.

With her pen moving quickly across the draft copy of the IEP, the vice principal made note of fears, desires, hopes, needs, dreams, and promises gone unfulfilled. Unsurprisingly to us, it became evident that with the fallout from the communication bombshell that had been dropped, we would not be signing a finalized IEP that day… unresolved concerns, unclarified needs, and unformulated strategies too numerous to count. With sincerity of heart in her eyes, the vice principal offered a full-length, fully-staffed follow-up meeting on a date of the mother’s choice, with the entire IEP team present and school district supports represented, alongside a sincere apology to us both for what had almost transpired: a casualty of federally-guaranteed services and supports for her son, lost to miscommunication.

***

Now I sit at a desk in another part of the city, still working to support families—including ones learning English —and their relationships to their school communities. I’m a few wrinkles and several years closer to wisdom, and the plentiful work to be done in South Carolina remains. But with shared commitment to the heavy lifting of linking arms with organizations and agencies to build trusted partnerships for school communities, stories like this one are becoming la excepción instead of la norma.

Share This Story:

Julia Beaty

As Bilingual Regional Liaison for the Carolina Family Engagement Center, based out of the SC School Improvement Council in The University of South Carolina College of Education, Julia is passionate about ensuring that both English- and Spanish-speaking children and families whose lives are impacted by disabilities and complex developmental trauma have access to multiple systemic supports. As a clinically-licensed Social Worker, Julia has worked with children and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities, as well as children impacted by developmental trauma. A Trust-Based Relational Intervention® (TBRI®) Practitioner, Julia has provided TBRI® Caregiver training for caregivers and professionals, both domestically and internationally. Please view her YouTube story!

Discovering Worth: There’s No Place Like an Educational Partnership with Families

The work of the Carolina Family Engagement Center (CFEC) is focused primarily on underserved families and their students (low income, English learners, those with disabilities, those in foster care, migrants, homeless, and marginalized communities). Housed within the SC School Improvement Council (SC-SIC) at the University of South Carolina College of Education, CFEC provides tools, trainings, and materials statewide through its website and other venues.

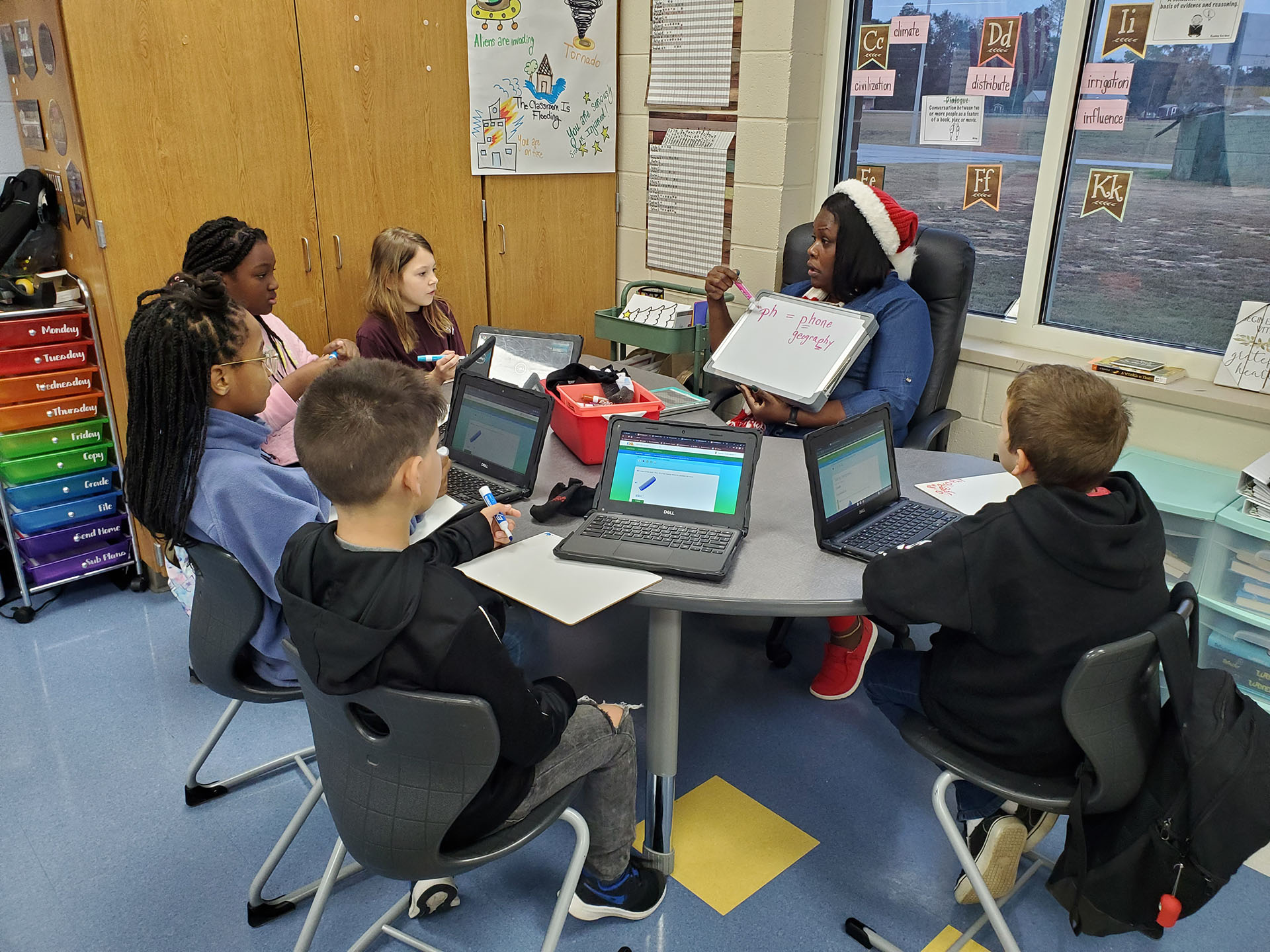

By: Ruth Hill, English Language Arts teacher, Simms Middle School

In the movie, The Wizard of Oz, the characters discover they have more potential for greatness than they previously realized. The Lion has courage, the Tin Man has a heart, and the Scarecrow has a brain. They just need the right circumstance to exercise their abilities. Dear little Dorothy realizes the worth of family and instills in us the timeless mantra, “There’s no place like home.” The viewer travels between two worlds – one magical and filled with possibilities, and one in which realistic values and ideals take precedent. Building educational partnerships with families does not need to exist in a fantasy world. Rather, valuable and worthwhile partnerships can be defined in both singular and multiple experiences that help us broaden the feeling of “home.”

One of the biggest obstacles I have encountered in my 26 years of teaching middle school students has been the lack of opportunity for family involvement in middle school children’s education beyond a couple of conferences a year. Have you ever wondered what an ideal partnership would look like at the middle school level? It is not a fantasy that our schools’ parking lots can be full of eager participants’ vehicles ready for Open House events, PTO meetings, book fairs, and other academic and extracurricular events.

The middle school years are crucial. Teachers and their students have a dire need for family involvement. When Dorothy saw that no one paid attention to her and the plight of her Toto (the most important thing in her life), she left. No need in staying around when she felt no one cared about her or her needs. But we do: educators and parents alike. Sometimes we may not feel equipped to help our middle schoolers with the things they are facing. It can feel easier to let them just run along or be alone — but we must reach out.

One of the most important ways we can do this is through family engagement activities. When families, schools, and communities work together, every child is successful. We’re setting a pattern for them to follow. For many years I have reached out to families so that they could experience writing together. The many workshops I designed have always started with a call to action, “You have a story to tell, let us help you tell it!” And for many years I struggled to find multiple families willing to participate. And then one perfect thing happened to me. I came across a grant in which an organization had my very goal in mind of engaging families to help students become more successful. With the help of the CFEC through the University of South Carolina I was able to address this very daunting obstacle with an array of support tactics.

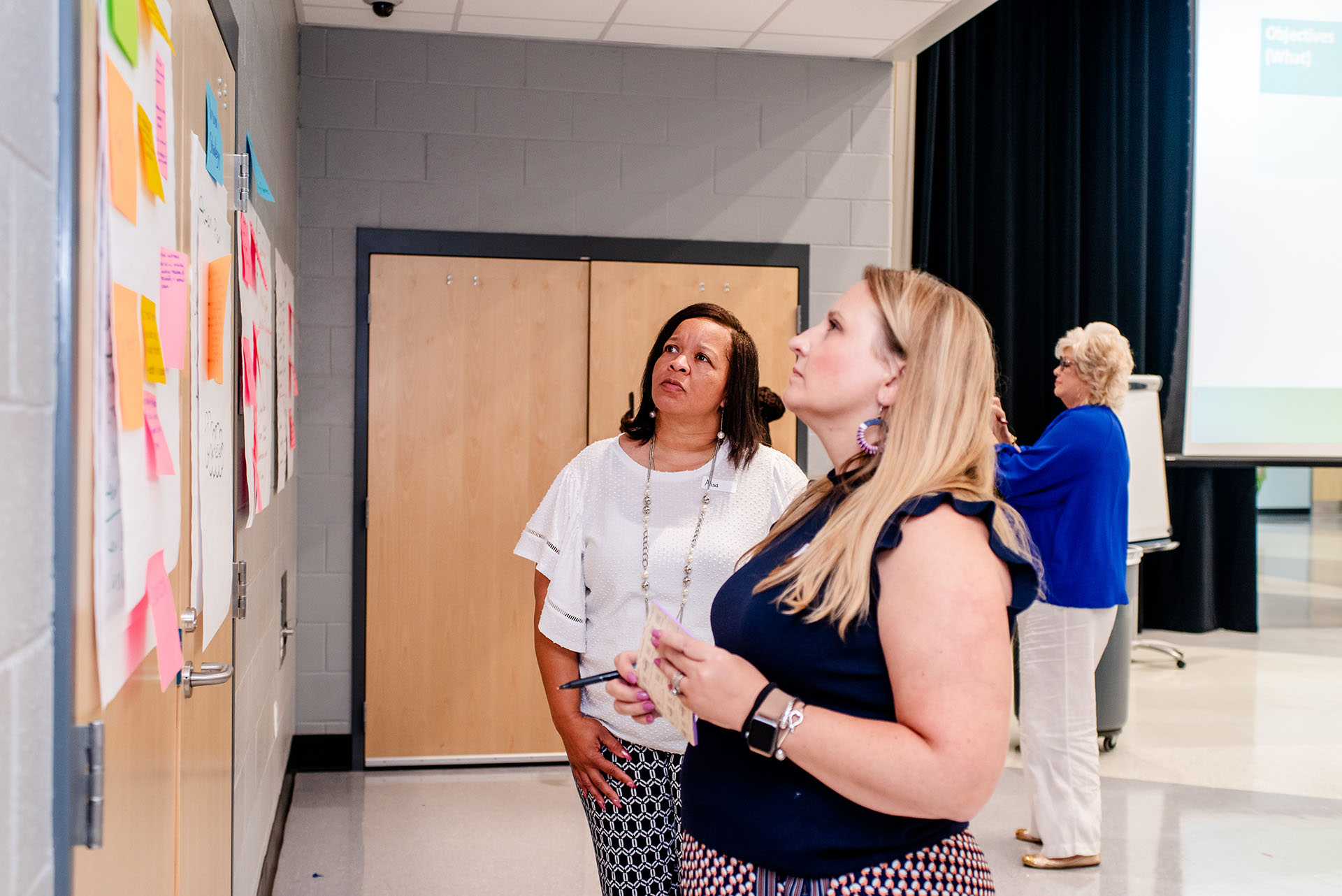

Ms. Julia Beaty was assigned as my liaison in helping me achieve the grand task, and together we put together a plan of action for family engagement activities. We started out with a conversation and built from this seed idea. As we came closer to the scheduled events, she contacted businesses who donated items, presented herself as a wise advisor, a creator of flyers, an instructional coach (for families as well as myself), technology advisor, and workshop presenter (Had I, myself, arrived in OZ?). My liaison helped put family engagement quality in perspective. While I thought numbers were the focus, she opened my eyes to see that it didn’t matter if there were only a handful of participants, what mattered was the quality of engagement for those of us in attendance.

When families, schools, and communities work together, every child is successful.

We dreamed together and shared the excitement of planning what we hoped would be quality engagement experiences and prepared for whatever the outcome would be.

Quality.

In middle school, many of our encounters with parents have a habit of becoming an experience dreaded by all

involved — parents, teachers, and students. These relationships are key for planning for deep family

partnerships. CFEC provided what I needed to have a different outlook on connecting with families, and the

experiences that came along the way have made a very enlightening “coming home” event for me, my students,

and their families.

Quality.

Last year’s Christmas event families came to share their favorite stories and recipes. We transformed the cafeteria into a winter wonderland. Tables were adorned with green and red tablecloths and ornaments, holiday books were available to read, a Christmas train traveled merrily around a track, and helpful handouts for publishing writing were strewn about. There was a table full of family resources from CFEC and the possibility of sharing with others as the Christmas spirit moved participants. Our decorating team consisted of my colleagues, my liaison, and me. All working beyond regular hours to make things beautiful so that families could physically experience something magical and meaningful.

Quality.

At this event, one mother came with a homemade key lime pie and a message. The topic of how our family recipes sometimes have a story was being presented as she entered, and the timing could not have been more perfect. The mom publicly shared how she made the pie from a recipe she learned in high school from a teacher she had admired. As she was telling her story, feelings of pride and connection filled the room. Other wonderful aspects of the event included a surprise visit (and compliments) from a congressman and active participation from administrators who stopped in to share in the festivities. All participants — teachers, parents, and students — were writing and sharing memories. We all went home a little taller that night.

Quality.

Like the time when our families gave us their hearts in a Valentine’s celebration we donned “Gather, Listen, Create, and Share!” One of the workshop events included a session titled “The Healing Power of Journaling: Because Black Mental Health Matters.” My liaison led a diverse group of participants through an activity called “Body Mapping.” During the event, one of the participants shared the impact of losing a loved one. His mother had no idea he had grieved in such a way. The activity called for participants to circle areas on the handout where they may have experienced something profound. The young male circled the space where the heart would be, and then he wrote about the significance of that circle. He let us in on the grief of losing his loved one. This was a total surprise to his mother who was also writing by his side. The event opened a door for the family to heal together. The impact that family engagement has on a child, witnessed firsthand, is full of visible worth.

Our middle school students need to be seen.

We have to let them know that we see them and that we know what they are going through — from the painful experience of losing a loved one to what may seem like a minor event that weighs heavily on their hearts and minds. They need to know they’re not alone and that we care. Our presence matters. Our mantra is “There’s no place like Sims, there’s no place like Sims.” (There’s no place like: insert your town/school here.)

Our middle school students need to be seen. Teachers need to be seen, too. Parents want to be seen.

Teachers need to be seen, too.

I want to be seen. I want to know that we are cared for and supported and that our time is valued and recognized. Teachers are not only instructors whose classes function live or flipped; we are also caregivers — making sure students are safe in our environment. As always we monitor, adjust, and thrive because we love and care about what we do.

Parents want to be seen.

They want to be recognized when they are experiencing the “coming of age” in their child (and sometimes have several ages in the home at once). They want to be supported through challenges, when setbacks with work, home, and school-aged children make them feel like they “haven’t got a heart, a brain, or the nerve.” We all need to define our worth and find “home” through our educational partnerships; for it is there where we can be that vital support to one another.

Quality.

“One of the most beneficial aspects of teaching is building positive relationships with parents. Effective parent-teacher communication is essential for a teacher to be successful.” (Meador). If we hope to see students grow to their full potential, we need not journey through these middle school years alone. Building educational partnerships with families can be defined in both single or multiple encounters that help us all to experience a sense of home. We all have what it takes to take this journey to its magical end. We just need to concentrate on the quality of the moments we share. In order to be productive we must internalize that #wearebettertogether.

But Oz never did give nothing to the Tin Man That he didn’t, didn’t already have… So please believe in me…

— Dewey Bunnell

**Meador, Derrick. “Cultivating Highly Successful Parent Teacher Communication.” ThoughtCo, Aug. 26, 2020, thoughtco.com/tips-for-highly-successful-parent-teacher-communication-3194676.

Share This Story:

Ruth Hill

Ruth Hill is a teacher at Sims Middle School in Union, South Carolina. She received a B.A. in Elementary Education and an M.A. in Gifted Education from Converse College in 1994 and 1998 respectively. Since her first day as a teacher through the present, her goal is to improve students’ literacy and to create activities for family engagement. In 2004, she became affiliated with the Spartanburg Writing Project and credits her reading and writing growth to SWP. She is a proud wife, mother of three, and grandmother to eight grandchildren who are the subjects and inspiration for picture books and young adult novels she hopes to publish one day.

Practitioner Inquiry: Supporting Teaching During a Pandemic

ABSTRACT

This article details the author’s practitioner inquiry project focused on examining teachers’ feelings about and uses of teaching with technology in a hybrid format during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data suggests that the Collaborative Inquiry Group (CIG) and administrative support provided to teachers influenced teachers’ positive views and experiences as they started teaching with technology.

NAPDS NINE ESSENTIALS (2nd Edition) ADDRESSED IN THIS ARTICLE:

- A professional development school (PDS) is a learning community guided by a comprehensive, articulated mission that is broader than the goals of any single partner, and that aims to advance equity, antiracism, and social justice within and among schools, colleges/universities, and their respective community and professional partners.

- A PDS is a context for continuous professional learning and leading for all participants, guided by need and a spirit and practice of inquiry.

- A PDS is a community that engages in collaborative research and participates in the public sharing of results in a variety of outlets.

- A PDS is built upon shared, sustainable governance structures that promote collaboration, foster reflection, and honor and value all participants’ voices.

- A PDS creates space for, advocates for, and supports college/university and P–12 faculty to operate in well-defined, boundary-spanning roles that transcend institutional settings.

Share This Story:

Brooke Scott

Brooke Scott is a former 3rd grade and 4th grade teacher and Customized Learning Coach. She is now an administrator at Oak Pointe Elementary School in South Carolina.

Culturally Responsive Teaching: From Individual Classrooms to Schoolwide Action

Introduction

It’s hard to admit you are wrong, and it is especially hard to realize you have biases in your teaching. This was my realization. I noticed my teaching practices were leaving many grade-level high school students disconnected, disengaged, and unresponsive. Sound familiar? The journey that followed this realization resulted in a career-altering transformation in my practice. I gained tremendous wisdom and compassion for others, but it wasn’t easy—and, fortunately, it didn’t stop with me.

As a result of lessons in the Fall 2019 “Introduction to Diversity” class at the University of South Carolina and participation in the Professional Development Schools (PDS) focus group at my school, I began to notice the students who were disengaged in my classroom were students of color. I realized that even with the best intentions, I was marginalizing students. I did not see my implicit bias, until one day…I did.

I saw that implicit bias validated some students while oppressing others. I saw the vulnerabilities of children whose identities were not validated by social structures. I saw how easy it is to believe the message of student deficiency and to normalize inequality. I wanted to do something about injustice—something that was in my power to do. I looked at myself and my classroom, and I began my own personal battle to combat this message so often communicated in schools across the country and that subsequently problematize inequality.

You see, as a white heterosexual female educator, I have never been told I could not do something because of the color of my skin or my sexual orientation. Even though I am a woman, my white identity has always been validated by structures in place. That gave me confidence, agency, and privilege.

My identity is not to blame. This is a societal problem where social signals reward some identities over others (Howard, 2010). However, with a little bit of effort on my part, in a short amount of time, I was able to break down some barriers for many students in my classroom through reflection and action. I began shifting my practice toward providing a more equitable classroom. I began looking for opportunities to include diverse cultures in classroom materials, dismantle impediments for diverse students, and create safe spaces to talk about sensitive, uncomfortable subjects like race and gender.

I had great successes with small changes such as providing more choice, co-creating culture projects with my classes, including students in classroom decisions, and sharing controversial topics associated with race and gender. As though I had sprinkled magic engagement dust throughout my classroom, disengaged students began to participate, complete their work, and influence others to do the same.

I saw students who had not turned in much work finishing their assignments early and being eager to present to the class. I heard kids say things like, “I’ve always been terrible at science,” start to see themselves as scientists. I saw increased self-confidence in science coursework for many diverse students. What I learned was that by being interested in learning more about my students’ cultures and deliberately valuing and including it in classroom materials and assignments, diverse student groups became interested in me and what I was trying to teach them.

James (pseudonym) stopped disrupting my class daily and started contributing. This once combative student suddenly began to pull his desk to the front of the room to ensure he didn’t miss anything. Because of the multiple changes that occurred in my classroom over that first semester, one particular adaptation does not stand out to account for this shift in James’s actions.

It was likely the combination of my choice to handle the disruptions confidentially and on my own without involving administration; explicitly speaking to his ability and positively about his identity as a black male; and the focus on building quality relationships. He knew where I stood and that place was as a supportive classroom member who just wanted him to be successful. This gave me an in to have the conversation with him about how distracted he was in class because of his cousin. That is when he started removing himself from the distractions by pulling his desk front and center. I helped him to recognize barriers in the classroom and to my astonishment he listened. He shifted from a distracted and disruptive student to a focused and engaged leader in the classroom.

Beyond Just Me

The impact of cultural inclusion did not stop with my classroom. The PDS structures in place provided an arena to share my transition with seven other educators in the 2019-20 PDS focus group at my school. Equity and cultural inclusion became the focal point of our conversations. In addition, cultural responsiveness became our school-wide goal.

This all happened before the coronavirus changed everything. When the revelation of inequities swept across our nation in the spring and summer of 2020, we were already working to combat injustice at our school.

In the spring of 2020, the PDS focus group decided to find a book focused on culturally responsive teaching practices geared toward application in the classroom. We decided on Sharroky Hollie’s (2018) Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Teaching and Learning. Of all the books available, we felt this book was most representative of best practices in the classroom for culturally responsive teaching.

The 2020-21 school year saw a 200% increase in participation in the PDS focus group, as 16 more teachers joined. Among the 24 of us participating in the book study are teachers in every content area committed to adapting our practice to be more culturally responsive to students.

PDS is revolutionizing education through the development of school-university partnerships and the empowerment of teachers. The existing PDS structures are designed to develop innovative programs to help teachers and schools become change agents and problemsolvers. At my school, teachers are awakening the most disengaged students through the interrogation of bias and inclusion of culture. The school-wide focus would not have happened had these PDS structures not been in place.

Yes, but How?

There are several adaptations I made to my classroom to make it a more equitable space for all students, including utilizing a family approach, building quality relationships, including different cultures, and having communal structures. These adaptations are explained below.

Family Approach

Like Gallagher (2016) discusses, I now approach issues in the same way an ideal, functional family would deal with problems. I hold the same expectations for my students that I do for my own children. If there are students experiencing challenges, they know we will work together until we reach a solution. Students need to hear that belief they can do it, so I give them multiple opportunities to demonstrate mastery and learn. In addition, I attempt to handle issues that arise by using a supportive family model, which means handling it internally with a caring approach. If there is a conflict, I try to resolve it with the student first to maintain confidentiality. This builds trust and lets them know they are important to our classroom. I do not call administration for small offenses. Another aspect of our classroom family is a buddy system, as discussed by Ladson-Billings (1995). Students have a buddy in the class for whom they are responsible. This builds peer social support and ultimately makes the classroom feel like a big family.

Relationships

I prioritize developing a relationship with every student that extends beyond academics. This might mean participating in a few TikTok dances and learning a few handshakes. This level of engagement grants me access to real conversations about students’ lives, goals, and the role of education, and the relationships we form gives me leverage to challenge them as learners, drawing on the importance of relationships as highlighted in the work of Howard (2013), Milner (2011), and Johnson (2011).

Cultural Inclusion

I use every opportunity to include diverse cultures in my classroom. Student work fills the room. Displaying student work communicates that I value students as a member of this classroom and see this as their space (Hollie, 2018). I practice equity by ensuring the images I use on my slides represent multiple identities and my classroom materials are inclusive. I share historical controversies in science surrounding race and gender inequality. We talk about uncomfortable issues. I share personal stories that are related to the content and encourage them to share personal stories, too.

Communal Structure

I relinquish control in my classroom whenever possible. Students are allowed to sit where they want, even if it is on the floor where we have beanbags. Whenever possible, I seek student input for classroom decisions. Some examples are student-created goals, choice in parameters for an assignment, and even order of learning. In addition, I plan opportunities for social interaction through collaborative work. This student-centered orientation of the classroom promotes equally valued perspectives on the content. Emdin (2007) calls this communal structure and suggests the corporate structures of teacher-directed learning and the hyper-structured classroom management of compliance causes diverse students to become disengaged.

Despite these changes in my practice, I still ponder, how many students am I missing? How many students are we missing, educators?

I challenge educators and leaders to begin or to continue your own personal journey of interrogating implicit bias. Do not let complacency interfere with student achievement. Inaction is action to reinforce bias. I challenge you to talk about race, gender, and other marginalized identities and their influences on the classroom. Diverse student groups need us to have those conversations, and it is to the benefit of all students when we center all cultures in our classrooms. I challenge you to watch students breathe a sigh of relief and feel safe when you see them and they see you. Mostly, I challenge you to try to incorporate culture in meaningful and authentic ways.

Share This Story:

References

Emdin, C. (2007). Exploring the contexts of urban science classrooms. Part 1: Investigating corporate and communal practices. Cultural Science Education, 2, 319-350.

Gallagher, K. (2016). Can a classroom be a family? Race, space, and the labour of care in urban teaching. Canadian Journal of Education, 39(2), 1-36.

Hollie, S. (2018). Culturally and linguistically responsive teaching and learning: Classroom practices for student success (2nd ed.). Shell Publishing.

Howard, T. (2013). How does it feel to be a problem? Black male students, schools, and learning in enhancing the knowledge base to disrupt deficit frameworks. Review of Research in Education, 37, 54-86.

Howard, T. (2010). Why race & culture matter in schools: Closing the achievement gap in America’s classrooms. Teachers College Press.

Johnson, C. C. (2011). The road to culturally relevant science: Exploring how teachers navigate change in pedagogy. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48, 170–198. doi:10.1002/tea.20405

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995a). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, 34(3), 160-165.

Milner, H. R. (2011). Culturally relevant pedagogy in a diverse urban classroom. Urban Review, 43, 66–89.

Brooke Biery (bbiery@lexrich5.org) is a science teacher at Dutch Fork High School in Irmo, SC where she is also a PDS Fellow for UofSC in the Curriculum and Instruction Education Doctorate program.

Robyn Brooke Biery

Brooke Biery is a science teacher at Dutch Fork High School in Irmo, SC where she is also a PDS Fellow for UofSC in the Curriculum and Instruction Education Doctorate program.

What Would Happen If We All Started Caring About Every Student?

In my more than 20 years of volunteering and working in public education in our state, I have never seen anything like what we experienced starting in the 2020 – 2021 school year. Teachers and students have always struggled, but we are at a critical crossroads. We were experiencing a teacher shortage pre-COVID with thousands of teachers not returning to teaching positions in their districts and teacher preparation programs not producing enough new graduates to fill vacancies. That was in addition to teacher burnout and ongoing COVID stress concerning the social and emotional wellbeing of students and concerns about teachers’ own health and safety. The survey “Teaching in South Carolina in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” conducted by the University of South Carolina, found that 80% of teachers surveyed are concerned about their students wellbeing. Here we are at the beginning of another year where COVID is profoundly impacting schools and schooling.

As I recall my days volunteering in the front office and in the classrooms at local middle and elementary schools, I witnessed firsthand some of the stressors that all teachers and support staff experienced on a daily basis. I also witnessed the passion and love they have for their students. Our teachers, administrators, and support staff truly care about the wellbeing of all students, and I could share countless examples showing how they have gone above and beyond for my own children. From attending baseball games to Ms. Pam in the cafeteria who always made sure my son had enough to eat for lunch (because she knew he was coming back for seconds). Our schools had a village vibe, and everyone looked out for one another.

The survey “Teaching in South Carolina in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” also showed that teachers have a deep commitment to students and their profession. They found new ways to collaborate with colleagues. The challenges COVID brought about spurred innovations in parent and family engagement, student centered learning, curriculum, and teacher leadership. So, while COVID amplified significant challenges in our state, it also gave our teachers and administrators the opportunity to think outside the box and reach out to colleagues for help.

Helping our teachers and our schools means helping our students. When our teachers feel supported, listened to, and respected these feelings flow to students. Just like many of our students, teachers often feel isolated and hopeless. In many parts of the state, they simply do not have the resources and the support systems in place for their own wellbeing, much less that of their students.

So, what can we do as parents and advocates?

Get involved

To take an even more active role in the life of your child’s school, consider serving on the local School Improvement Council.

I realize that many parents and caregivers are just trying to survive day to day (I’ve been there, too). But there is always a way we can be involved. From simply attending the parent/teacher conferences to making sure your student is showing up in-person and online. Communication between parents/caregivers and teachers is a critical component to student success. If teachers aren’t aware of obstacles prohibiting student success they can’t proactively support solutions. Teachers want students to succeed, and they are willing to work with us; they just don’t always know what outside stressors or issues we are dealing with at home.

If you have more time on your hands, find a way to volunteer. Whether learning is happening in-person, online, or in hybrid environments, teachers and schools will always need our help and often times they won’t ask for it. Don’t be afraid to send an email offering to help and asking what you can do. I am fairly certain that they will have a task or two for you! If not, consider helping via your local SCPTA or other parent organization. Many of these organizations also offer numerous support systems for parents and caregivers. To take an even more active role in the life of your child’s school, consider serving on the local School Improvement Council. The SIC is made up of all constituency groups in a school – including parents – and works specifically to strengthen school and student outcomes.

Stay up to date on what is going on in the district through local board of education meetings. Sometimes we get so focused on what is going on with our own student(s) that we forget that decisions made at a district level have a huge impact on all students. The South Carolina School Boards Association has a list of all 79 districts with the names of their board members. They also have an advocacy section where you can find legislative priorities and a current list of local legislators.

Ask questions.

It can be challenging to decipher the educational lingo that often comes home with students, so don’t be afraid to ask questions. Chances are if you don’t understand it, there are others having the same issues.

Francis Kepple, former U.S. Commissioner of Education for Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, put it this way: “Education is too important to be left solely to educators.” This can serve as a call to parents and advocates to do what they can – individually and collectively – to support their schools, teachers, students, and communities.

The more we ask questions and the more involved we become, the more we start making decisions that will not only have an impact on our students but every student.

Francis Kepple, former U.S. Commissioner of Education for Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, put it this way: “Education is too important to be left solely to educators.” This can serve as a call to parents and advocates to do what they can – individually and collectively – to support their schools, teachers, students, and communities.

It doesn’t take a huge leap to go from caring about your child to caring about all students; even the smallest of steps can make a huge difference.

This story is published as part of a storytelling retreat hosted by the Center for Educational Partnerships (CEP) housed in the University of South Carolina’s College of Education. CEP partners nominated practicing educators, administrators, and system leaders to share their stories. The Center for Teaching Quality (CTQ), a CEP partner, facilitated the retreat and provided editorial and publication support. Learn more about this work and read additional stories by following @CEP_UofSC and @teachingquality.

Share This Story:

Debbie Jones

Debbie Jones, a native of Virginia, has lived in Florence, SC for over twenty years. After volunteering with The School Foundation, a local education foundation in Florence, she began working with South Carolina Future Minds where she was a founding staff member.

Ms. Jones is a graduate of Meredith College and served in a variety of leadership roles at the local and state levels, including the SC PTA, YMCA Florence, and Emerging Leaders Florence. She is a 2020 Riley Fellow, 2020 Public Education Policy Fellow, and graduate of the Non-profit Leadership Institute at Francis Marion. She currently serves on the board of SC First Steps of Florence.

The Power of Stories from the Inside Out

“Silence is the enemy of justice.” – Aline Ohanesian, Orhan’s Inheritance

Far too many educator stories go untold. As the most observed profession of all professions, the stories of teachers and teaching have been published by a variety of stakeholders, often well meaning, yet missing the authentic lens of the practitioners who engage with students daily. The half dozen stories assembled here only begin to scratch the surface of exposing the power of storytelling from educators’ point of view. What fuels their power? Their expertise and a desire to share it. Their isolated practice and a desire to overcome it. Their commitment to service and a desire to deepen it.

These stories break the deafening silence. They offer lessons that we as citizens in a democracy need to be reminded of and re-tell and re-invent as our own experiences are shared. These educator authors remind us through compelling nonfiction narratives to use all tools at our disposal to see and hear others; to lean into our own discomfort in order to model growth and learning; to explore connections between science and social justice; to invite the authenticity of every voice to lead classrooms and schools of celebrated inclusivity and belonging; to use the power of empathy to advocate for change through activism; to share classroom power to build powerful learning; to embrace the change that accompanies meeting each student where they are.

All of these stories are about voices, many voices: parents, children, principals, teachers, educators in a variety of roles, the community that envelopes each and every school. These half dozen stories are compelling and authentic. And for each one of these, there are thousands more that never get told.

Why? Many reasons. We don’t think to ask. We think we “know” the stories since we were all students once and “watched teachers” do their work – an act sociologist Dan Lortie called “apprenticeship of observation” to describe the thousands of hours we spend as students observing and evaluating professionals in action (Schoolteacher, 1975).

Giving the public access to insights that often remain unexplored and, if explored, often unshared, strengthens our democratic society as educator professionals model a civic responsibility of sharing voice in the spirit of educating citizens of all sectors.

Providing opportunities for practitioners to tell their stories helps to bring hazy perceptions into clearer focus. It also creates some rare space and time for educators to deeply reflect, analyze, and share some of their more profound work as learners of their chosen profession that ironically is all about learning. This necessity is too often pushed aside because of competing priorities, creating counterproductive choices as educators lose opportunities to think, refine, and revisit their practice. Giving the public access to insights that often remain unexplored and, if explored, often unshared, strengthens our democratic society as educator professionals model a civic responsibility of sharing voice in the spirit of educating citizens of all sectors. And, crafting these stories not only provides insights for the audience, they clarify learning and strengthen the voice of the storytellers. The more we are able to practice the art of storytelling, the more opportunity we have to connect in meaningful discourse.

Recognizing the opportunity to share powerful experiences of educators in the University of South Carolina (UofSC) network of partners, the Center for Educational Partnerships invested in a storytelling retreat attended by the six authors featured in this journal (plus 18 more storytellers). All stories produced from this writing retreat have been published in some format, completing a necessary and final step of validating the writing process for each author.

Educators report that they have grown from being able to tell their stories, and their sense of professionalism has been enhanced by having their voices published, as evidenced in the quotes below from storytellers:

- “There are so many stories, and mine is more important than I would have thought.”

- “I feel inspired to tell my story, my truth, my experience.”

- “I didn’t give myself credit for understanding that my story may have a positive influence on others.”

As a Research 1 University, certainly the College of Education values the scholarly work of its faculty. And as the flagship University in the state, there is unapologetic value placed on innovations and collaborations that provide other types of South Carolina-centric data such as the lived experiences of educators who are in schools and classrooms every single day. Each of these authors told their own story without concern for if, where, and how they would be published. The surprise of the storytelling was that several groups of writers focused on similar topics that could become a collection like these stories.

When UofSC identified an interest in helping educators find their voice through storytelling, they turned to a highly-respected national non-profit organization, the Center for Teaching Quality (CTQ), for facilitator expertise. The first retreat was such a success that the partnership between CTQ and UofSC around storytelling continues to expand. CTQ uses a suite of storytelling tools and protocols specifically designed to assist participants (of wide-ranging experiences as writers) in examining the impact of their work.

The approach to do so involves taking a general anecdote into a deeper analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data, and then stepping back to take time to answer “So what?” from as many perspectives as possible. And, once the storyteller lands on the lens of the story that will likely bring about the most powerful response – A CALL TO ACTION – then the story has its shape and purpose. What’s left is to ensure lessons to be shared are as clearly and compellingly communicated as possible.

Perhaps the most powerful part of this storytelling approach is the “peer writing workshop” sessions where participants work in small groups to listen and respond to one another’s stories. The TELLING of the story breaks the isolated, and often suffocating silence of untold stories set in classrooms, hallways, offices, lunchrooms. And the value of honoring the experience and voice of educator storytellers and those they serve is what makes public education a cornerstone of our democracy. One that must be celebrated through stories from the inside out.

As you have engaged with this collection of stories, we hope you have been inspired to further explore how spreading stories in your own practice would add even more value to your work.

What’s your story? We look forward to hearing about it.

Share This Story:

P. Ann Byrd

P. Ann Byrd serves as President & Partner of CTQ, a national nonprofit focused on advancing the collective leadership of teachers and administrators working together to transform their profession. She spent 13 years teaching high schoolers (English Language Arts and Teacher Cadet) before joining CERRA’s staff for 10 years at Winthrop University, the last six as Executive Director. She earned National Board Certification in ELA/AYA (2000/2010) and also served six years as a member of the NBPTS Board of Directors. Ann holds a B.A. in English–Secondary Education and an Ed.D. in curriculum and instruction from the University of South Carolina. Her purpose-driven investment in collective leadership creates space for her to work alongside dedicated educators throughout the country to make schools better for all students.

Cindy Van Buren

Cindy Van Buren has been an SC educator since 1988. She has previously served as the Deputy Superintendent for the Division of School Effectiveness for the South Carolina Department of Education, the Chair of the Department of Education at Newberry College, the Director of Teacher Education at Winthrop University, and as a high school administrator and teacher at Rock Hill High School. Since joining the staff in the College of Education at UofSC in 2015, she has dedicated her work to building and maintaining partnerships that improve the lives of teachers, students, schools and districts in SC. As assistant dean for Professional Partnerships in the College of Education at UofSC, she serves as the Director of the Center for Educational Partnerships and CarolinaCrED. P. Ann Byrd serves as President & Partner of CTQ, a national nonprofit focused on advancing the collective leadership of teachers and administrators working together to transform their profession. She spent 13 years teaching high schoolers (English Language Arts and Teacher Cadet) before joining CERRA’s staff for 10 years at Winthrop University, the last six as Executive Director. She earned National Board Certification in ELA/AYA (2000/2010) and also served six years as a member of the NBPTS Board of Directors. Ann holds a B.A. in English–Secondary Education and an Ed.D. in curriculum and instruction from the University of South Carolina. Her purpose-driven investment in collective leadership creates space for her to work alongside dedicated educators throughout the country to make schools better for all students.

Power Up by Giving Up Power

In May of 2020, my fourth grade students presented their TED Talks to our class via Google Meet. This was something my students had poured their hearts and souls into for four months. I was not going to let a pandemic stop our class experts from sharing their knowledge on topics they were passionate about. When I started this process, I had no idea how it was going to turn out. I had no idea that Omar, one of my students, was going to teach me by sharing an understanding and perspective that I had never considered before.

Omar’s topic for his TED Talk was xenophobia. Omar is Muslim. As he prepared for and presented his talk, he openly shared his own and others’ experiences with racism and anti-Muslim acts. His pain and sadness about this hatred was evident through the words he chose, the way he spoke, and the emotions he showed as he shared his thoughts. Giving Omar the time and space to research a topic and the power to have a voice taught all of us what it is like to be Muslim in America.

Today, there is an educational movement focused on student-centered learning. As a doctoral candidate in Curriculum and Technology at the University of South Carolina, I have focused my research on utilizing inquiry to deepen student understanding on topics that are personal to them while also addressing the standards. Inquiry is one way to make learning student-centered, as it allows students to share in the holding of power regarding knowledge in our classroom. This is accomplished by the teacher removing themselves as the “knower” of all information.

When I positioned myself as a learner alongside my students, I gave them power to utilize inquiry, to become experts on topics, and to be the primary holders of knowledge.

TED Talks allowed my students to draw on their own experiences, knowledge, and passions to choose topics they wanted to learn more about. They became class experts on real-world problems and issues as they utilized the inquiry process, and they developed voices that were truly heard and honored. Allowing my students to share in the power paid off as students were engaged and had the opportunity to authentically learn from one another. I watched the students in my classroom shift from shock to understanding and empathy as Omar shared his personal and heartfelt TED Talk. This meaningful moment would have never happened if I was the one holding all the power and delivering the information.

For power to be accessible to both teachers and students in a classroom, the culture of the classroom must be one in which students know they are valued and there is an understanding that they can be a “teacher,” too.

For power to be accessible to both teachers and students in a classroom, the culture of the classroom must be one in which students know they are valued and there is an understanding that they can be a “teacher” too. This culture evolves through mutual respect for one another, allowing time to talk and share, and honoring and celebrating differences. For me, a white woman, I understand that I will never have some of the experiences that the students in my class will. Having a classroom culture of acceptance and inclusivity allows us to learn from one another.

It creates a space for all students to hear other voices and perspectives. This results in achievement and engagement.

As Omar prepared for his TED Talk, he touched my heart during a writing conference as he spoke about the stigmatism associated with 9/11 and Muslims in America. He shared his frustration that his name was the same name as one of the hijackers of the airplanes. His love for America is deep, and he was hurt by the events of that day and his own connection to it. I learned so much from Omar as I gained understanding about the Muslim experience through his eyes. The learning for me extended beyond the walls of the school as Omar and his family taught me about Ramadan and invited me to have a glimpse into their beliefs and traditions.

We, as teachers, have so much to learn from our students. If schools truly want to be about their students and their learning, then they need to give students time, space, and power to become experts on topics that matter to them.

We, as teachers, have so much to learn from our students. If schools truly want to be about their students and their learning, then they need to give students time, space, and power to become experts on topics that matter to them. Students need to know we will listen to their authentic voices and that they will be heard. They need to know that we, their teachers, want to learn from them. By doing this, students can have real ownership of their learning and can become powerful lifelong learners.

Share This Story:

Brandy Meyers

Brandy Meyers is a 4th-5th grade teacher at Oak Pointe Elementary School in School District 5 of Lexington and Richland Counties. Brandy received her undergraduate degree in Elementary Education and a master’s in Language and Literacy from the University of South Carolina. In 2021, she earned her doctorate in Educational Practice and Innovation from the University of South Carolina. Brandy enjoys being at a University of South Carolina PDS school and learning alongside her students, interns, and colleagues.

Everyone Can Be “Au-Some”

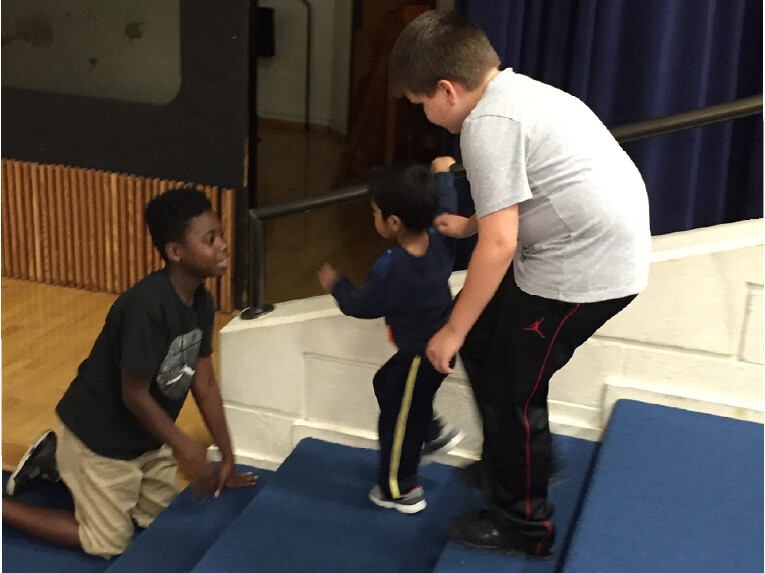

As I walk down the hall of Harbison West Elementary school, I hear a large commotion coming from the area by the cafeteria. It’s past 1 p.m. so I know it’s not lunchtime anymore, but the noise continues to grow. I hear laughter, cheering, and music playing. Once I turn the corner and get a view of the cafeteria, I see a group of fifth-grade students playing with a parachute, bowling balls rolling down a line toward small plastic pins, and bubbles in the air. I have just walked in on Project Au-some’s endof-year celebration.

I immediately catch the eyes of a student we will call Dylan, whom I have watched struggle academically and behaviorally through the years. He is a quiet force to be reckoned with. You know those students, the ones too “big and bad” to be doing anything at school. When the fifth graders began visiting the preschool classroom, Dylan was often apprehensive and disengaged.

I scan the rest of the cafeteria and watch as the fifth grade students take their “Little Buddies,” (our preschool special education students) through different stations set up throughout the cafeteria. I smile. I look back at Dylan as he approaches Laura. Laura is one of the preschool students who uses a wheelchair and has severe delays in communication and motor skills. She is sitting on the sidelines with her aide. After Dylan and Laura’s aide exchange words, Dylan takes Laura through the parachute. I stand there speechless — I’m in awe of what is taking place.

Dylan was the only student that day that noticed Laura wasn’t engaged in any of the activities. Her aide was sitting with her on the sidelines and having her “watch” the fun. For Dylan, that wasn’t enough. He became her sidekick during the celebration and ensured that she was an active participant for the remaining stations and games. This is one of the many stories of fifth graders at Harbison West who have participated in Project Au-Some. Students continue to grow their social-emotional skills through exposure, experience, and teaching.

Exposure isn’t enough. We leverage this amazing opportunity to teach students about disabilities and diversity within those experiences.

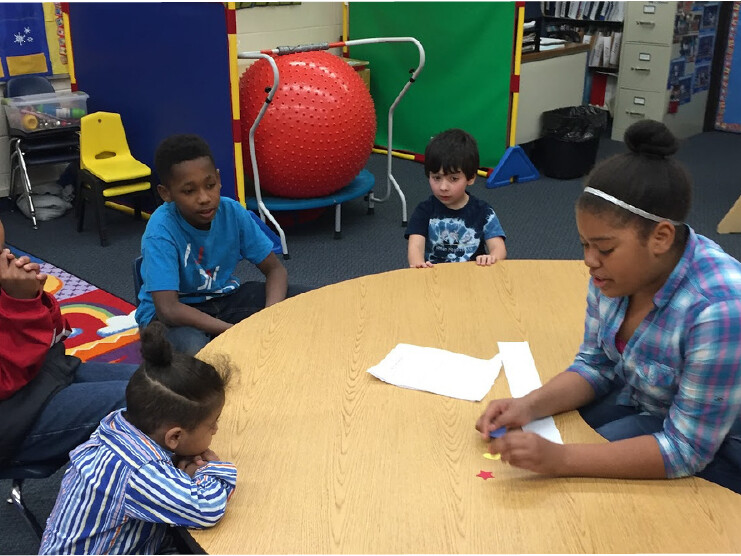

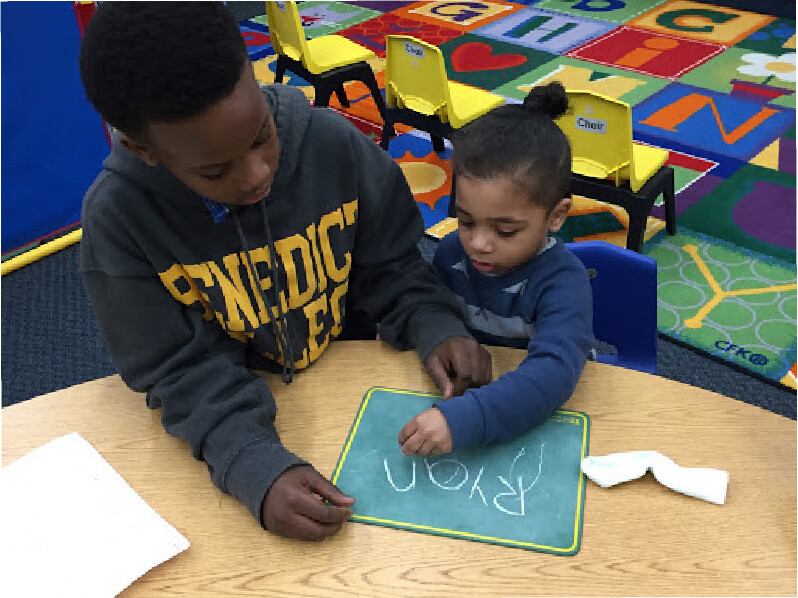

Project Au-Some began in 2015. It is a concerted effort to build empathy and acceptance within fifth grade students, as well as build social skills within preschoolers with special needs. The purpose of Project Au-Some is to take opportunities teachers create for exposure and teach practical social emotional learning skills through these experiences. Our exposure begins with teacher-led activities within the classroom. By providing exposure we can do great things, but it doesn’t end there. Exposure isn’t enough. We leverage this amazing opportunity to teach students about disabilities and diversity within those experiences.

After each visit, I (as the special education teacher) take the students to a quiet area to reflect. Through these reflections teachable moments surface. I begin by asking open-ended questions including: What did you like? What surprised you? What scared you? What would you do next time? After an open discussion, each “Big Buddy” has an opportunity to draft a written reflection. In these reflections, students began asking for more and advocated to plan and teach lessons. While I worked hard to ensure students had opportunities to build and grow themselves, I also realized through listening that this could become much more than we ever imagined. By teaching about behaviors and reflecting on their experiences, it empowered the fifth graders to lead.

These images capture a few of the lessons developed after choosing an objective from a list of developmental skills, then planned and taught by the fifth graders. But this was only the beginning. The students began to research different disabilities and found that our library housed only two books that featured students with disabilities. We wrote grants to gather more books and the students created the PAL (Project AuSome Learning) Library that now has more than 250 books.

Throughout the years our fifth graders have chosen to be community activists for change. Each year they select a different organization to write to for their opinion writing project.

Throughout the years our fifth graders have chosen to be community activists for change.

In the spring of 2017, our fifth graders learned about the adaptation of one of their favorite books, “Wonder” by R.J. Polaccio. Each student wrote to the Children’s Craniofacial Association (CCA) requesting our school host a premier of the movie. In the Fall of 2018 we received a call from the director of the CCA and became a premier presenter. We raised money and Project Au-Some provided a free viewing for more than 700 students and families. Our students’ letters to CCA were displayed to promote the work they did to make changes within their community.

Students were invited back to experience the day, demonstrate that they have the power to change lives, and understand that their words and actions hold lasting meaning.

Project Au-Some students have changed minds, lives, and perspectives. It all started with taking opportunities for exposure and creating moments to intentionally teach. Not only did these opportunities provide a platform for action, but they also changed the fifth graders’ perspectives. Students were given an empathy survey at the beginning and end of the year to help document their experiences and measure how their mindsets changed. In three years of documentation, we have seen an average of 78% growth in our fifth graders. We have seen students like Dylan grow from 15 to 35 points on the empathy scale.

Students are continuing to write their stories while growing in their compassion and empathy because a group of teachers knew exposure alone wasn’t enough.

Students are continuing to write their stories while growing in their compassion and empathy because a group of teachers knew exposure alone wasn’t enough. Have you given your students the ability to learn about diversity and differing abilities?

Have you given your students the ability to make connections across grade levels? If not, I encourage you to give your students the opportunity to lead and learn about diversity and disabilities. The opportunity to ask questions and be exposed to others that are different from themselves. The opportunity to be agents of change.

It starts with you.

Share This Story:

Bethany Reilly

After earning her degree in Special Education from Winthrop University, Bethany Reilly entered the classroom and found her passion for working with students on the Autism Spectrum. Bethany has been teaching for the past 14 years, working with students ranging from early childhood to elementary special education. She continues to support the inclusion and acceptance of all students and teaches diversity awareness school-wide with the Project Au-Some team at Harbison West Elementary in Columbia, South Carolina.

Can You Hear Me?

“Can you hear me? Can you see me?”

These are the first things we hear as students log in to their virtual classrooms, clients log in for virtual telehealth counseling sessions, or our colleagues log in to virtual meetings. Due to the pandemic, many of our interactions with others now take place in a virtual space. However, “Can you hear me? Can you see me?” are not questions that are unique to the use of virtual platforms.

Humans are relational beings. We need our voices to be heard, to feel seen, and to be validated. We need to connect to others to be our best selves. Our students, clients, and our children ask, “Can you hear me?” and “Can you see me?” multiple times a day. However, they usually do not use these words; they use behaviors.

I am reminded of the many children I worked with as a full-time professional counselor. One in particular asked “Can you hear me?” and “Can you see me?” to every adult he encountered. Jacob was a tall, skinny, five-year-old, African American boy in kindergarten. After a couple of weeks meeting with Jacob in my office, I was asked to observe him in his classroom as his behaviors were escalating.

Jacob had transferred to a new school halfway through the first quarter. His teachers described him as loud, aggressive, disrespectful, and a distraction to his classmates. His principal said he was not completing any of his work, his behaviors were erratic and unpredictable, and that she believed he was “psychotic” and in need of medication.

On observation day I enter the back of his classroom and sit in a corner. Jacob was not aware I was coming and did not see me enter the room. I watch Jacob sit calmly and quietly at his desk in the back row with a piece of writing paper and pencil. He is watching his teacher explain to the class that they are practicing writing their names. She instructs the class to begin practicing and says she will stop them in about five minutes to move on to the next writing activity.

Humans are relational beings. We need our voices to be heard, to feel seen, and to be validated. We need to connect to others to be our best selves. Our students, clients, and our children ask, “Can you hear me?” and “Can you see me?” multiple times a day. However, they usually do not use these words; they use behaviors.

Jacob begins writing his name. After a few marks, he lets out a small huff and starts erasing. He begins writing again and very soon after, erasing…again. He continues with the process of writing and erasing, writing and erasing, writing and erasing, for the entire five minutes. Each time he stops, he lets out a small huff or pounds his fist on the desk in frustration. After the five minutes are up, his teacher asks the students to stop and take a seat on the floor in front of the chalkboard to transition to the next activity. Jacob, (without raising his hand) says, “I’m not finished with my name.” His teacher responds, “You had plenty of time to write your name. You shouldn’t have wasted your time.” Jacob replies, “I kept messing up. I need more time.” His teacher asks him to join the rest of the class on the floor. Jacob gets angry, rips his paper, and storms to the other side of the room where he sits on the floor away from the other children. He says he is going to read instead of listen to her “stupid directions.”

“Can you hear me? Can you see me?”

The teacher continues the lesson and has the children help her spell out words like pumpkin, orange, and Halloween as she writes them on the board. Jacob continues to sit on the floor, removed from the class, book open but upside down. As the teacher works with the class spelling out words, Jacob peeks over the book at the board and follows along, mouthing the letters to himself.

After all three words are on the board, the students return to their seats to copy the words onto their papers. Jacob returns to his seat slowly and with his head down mumbles to the teacher, “I need a new paper.” His teacher responds, “Why did you rip up the other paper?” Jacob replies, “I was mad.” His teacher continues to tell him that he needs to treat his things with respect as well as respect her and then hands him a new paper.

“Can you hear me? Can you see me?”

Jacob stares at the board from his seat in the back and gets up to move closer. His teacher asks him to sit down. Jacob explains that he can’t see as he continues to walk to the board. Jacob’s teacher walks over to Jacob and tells him he needs to sit down and if he doesn’t he will get his star moved from yellow to red (it was already moved from green earlier in the day). Jacob throws his paper, kicks the desk in front him, and turns around to walk away.

Then he sees me.

He sits down and begins to cry. I walk over to Jacob and he immediately asks me, “What are you doing here?” I tell him I am here to see him. He stops crying and shows me his cubby. We move to the side of the room and color together. I ask what the other students are doing. He tells me about the writing activity and he says it was “stupid” and he “can’t do it right.” I ask if he wants to do it with me and he says, “Okay.” As Jacob works, he gets frustrated and stops. I provide encouragement, reminders that it is practice and doesn’t need to be perfect, and that I can see he is working hard. He ends up finishing the activity and is excited to show his teacher all the words he has written.

“Can you hear me? Can you see me?”

What I see is a little boy trying to do his work, wanting to do his work, but struggling and getting frustrated.

What I hear is a child asking for what he needs with words, body language, and behaviors.

What I see is a child who wants to learn.

What I see is a child paying attention even if it isn’t in the same way as the other students.

What I see is an emotionally drained and frustrated child who struggles with self-esteem.

What I also see is an overwhelmed teacher — a teacher who has many children in her class with individual needs, a teacher that wasn’t listening with her eyes and missed Jacob’s desire to learn, a teacher who is doing the best she can but lacking tools of awareness and an understanding of how to see this child.

Jacob was not “psychotic” or intentionally disrespectful. Jacob was tired, sad, and angry…Jacob was also sweet and caring. He was strong. He was creative and had a great smile. He was smarter than he believed himself to be, AND he needed to be seen, heard, and noticed.

Jacob transferred to the school in October because his mother was unable to care for him and his siblings. Jacob’s mother brought her children to the Department of Social Services while she attempted to find a better job and housing for their family. Jacob was separated from all his siblings and moved to three different foster homes in less than two months. Jacob witnessed domestic violence, neglect, and abuse from his mother’s previous boyfriends from a young age.

“Can you hear me? Can you see me?”

Jacob was not “psychotic” or intentionally disrespectful. Jacob was tired, sad, and angry. He missed his siblings and his mother. He was adjusting to being in school for the first time. He lacked consistency. Jacob was also sweet and caring. He was strong. He was creative and had a great smile. He was smarter than he believed himself to be, AND he needed to be seen, heard, and noticed.

As a professional counselor and a counselor educator, I have learned, (and continue to learn), to listen with my eyes and not just my ears. I try to see what the child is communicating through their behaviors or actions. Is the child acting out in class truly angry at his classmate for knocking his elbow as he is writing or is he tired and irritable because he doesn’t sleep well at his dad’s new house? Is the child that can’t sit still, intentionally not focusing on the teacher’s lesson or is she anxious or scared due to living in a home with domestic violence?

As the Program Manager for the Carolina Transition to Teaching Residency at the University of South Carolina, I was unsure how my professional background would be helpful in a teacher education program. However, I quickly saw the need and the desire of our teaching residents to connect with their students and attend to their students through a more holistic lens. The residents were bursting with passion to help the children in their classes and eager to build a sense of community in their own classrooms. To answer this need my colleagues and I created a social-emotional learning professional development series throughout their time in the program. The focus of the social-emotional learning series is twofold. First, the residents are learning to understand their own social-emotional needs. By better understanding their own social emotional needs, they are better able to understand their reactions to students, increase empathy and patience, and enhance curiosity about their students. Second, the residents are learning how to facilitate social emotional learning in their own classrooms. The residents are learning to see the impact of getting to know their students — to see their students with more than their eyes.

Although it is not the teacher’s job or focus to provide counsel to students, teachers are on the front lines. Teachers are the ones that know the pulse of the school and student body. During the school year, teachers are the adults that interact with children the most. If aware, teachers have the power to notice subtle and overt changes in students and connect them to those who can help. Teachers are more than educational tools or vessels of knowledge; they are the eyes, ears, and voice of our youth. AND they need tools to help them see, hear, and advocate for our children.

Teachers are more than educational tools or vessels of knowledge — they are the eyes, ears, and voice of our youth. AND they need the tools to help them see, hear, and advocate for our children.

“Can you hear me? Can you see me?”

All eyes to the front of the room, please.

“Can you hear me? Can you see me?”

Please stop fidgeting with your pencil.

“Can you hear me? Can you see me?”

Please keep your head up and not on your desk.

“Can you hear me? Can you see me?”

That’s not the way we speak to our classmates. Please apologize for being rude.

“Can you hear me? Can you see me?”

“Can you see that I am nervous? Stressed? Tired? Hungry?”

“Do you know the things I am responsible for at home? That I want to be here, and I like your class? That I want to learn? That I have many strengths and not just needs?”

“Hear me.”

“See me.”

“Know me.”

Share This Story:

Jessie Guest

Jessie Guest received her Ph.D. in Counselor Education and Supervision from the University of South Carolina (UofSC). Jessie is a Licensed Mental Health Counselor, teaches graduate courses in the Counselor Education Program at UofSC, and is the Program Manager of the Carolina Transition to Teaching Residency Program focused on teacher preparation and retention in rural counties throughout South Carolina.

When the Spirit Speaks: My Battle with Change

Have you ever loved something so much that it made you crazy? Perhaps not in the sense of being deranged, but out of your mind. Maybe even literally?

I was a teacher. A song-singing, esteem-building, dataanalyzing teacher. I poured everything I had into my chosen profession, and I reaped the benefits. Being with my students gave me energy, and that energy fueled more creative ways to reach them. Throughout my eleven years as an educator, that never changed.

That never changed.

The legislation changed. The standards changed. My schools changed. I changed states.

There was always change.

So, I taught my students to be lifelong learners and conditioned myself to do the same. Each time change reintroduced itself, I embraced it. After all, it was an opportunity to learn something new.

Then one day, the turns of each change left me emotionally entangled and sobbing on my classroom floor. In that moment, my personal expectations of motherhood became the bricks that weighed on my chest, while each task at work built the walls that enclosed me. The safety net that I crafted from tenacity, perseverance, and flexibility crumbled. And there I was, drowning in obligation and sinking in a pit of change.

How did I get here? How could this be happening to me? Was I dreaming?

As I stand in the gift of hindsight, I now realize that I should have seen it coming. My behavior patterns were shifting around the same time I experienced my meltdown. My attention to detail and passion to engage in critical dialogue were no longer a match for the endless emails and piles of grading. The internal struggle was overwhelming. My duties and my desires were set against each other on a pendulum.